The Trump administration’s escalating clash with the judiciary over immigration, spending priorities and more is turning previously unknown judges like James Boasberg and Paula Xinis into household names.

The judiciary has been a notable battleground in President Trump’s first year back in office, particularly given Congress’s compliance with his vision.

More than 500 legal challenges have been mounted against Trump’s second-term agenda, making the courts the front line in the president’s effort to reshape much of the country.

While judges have at times blocked Trump’s progress, they also have attracted the ire of the president and his team.

“They have a robe on, but they are more political or certainly as political as the most liberal governor or D.A.,” Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche said at a November conference for conservative lawyers.

“There’s a group of judges that are repeat players, and that’s obviously not by happenstance; that’s intentional,” he continued. “And it’s a war, man.”

It’s not unusual for judges to assume greater public visibility amid consequential court cases.

When Trump faced four criminal indictments and a slew of civil matters, federal judges like Aileen Cannon and Tanya Chutkan — plus state judges like Juan Merchan, Arthur Engoron and Scott McAfee — were both vilified and celebrated for their roles in the cases.

Boasberg, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia’s chief judge, has faced more scrutiny than most since Trump’s return to power.

An appointee of former President Obama, Boasberg took center stage in March when he was assigned to oversee a lawsuit challenging Trump’s invocation of the Alien Enemies Act.

The judge swiftly barred Trump from deporting alleged Venezuelan gang members to a notorious megaprison in El Salvador under the wartime law and verbally directed officials to halt or turn around any planes carrying noncitizens covered by the order.

At a pivotal hearing days later after some flights continued, Justice Department lawyers refused to answer certain questions and claimed Boasberg’s oral command wasn’t binding because a later written order failed to mention already-airborne flights.

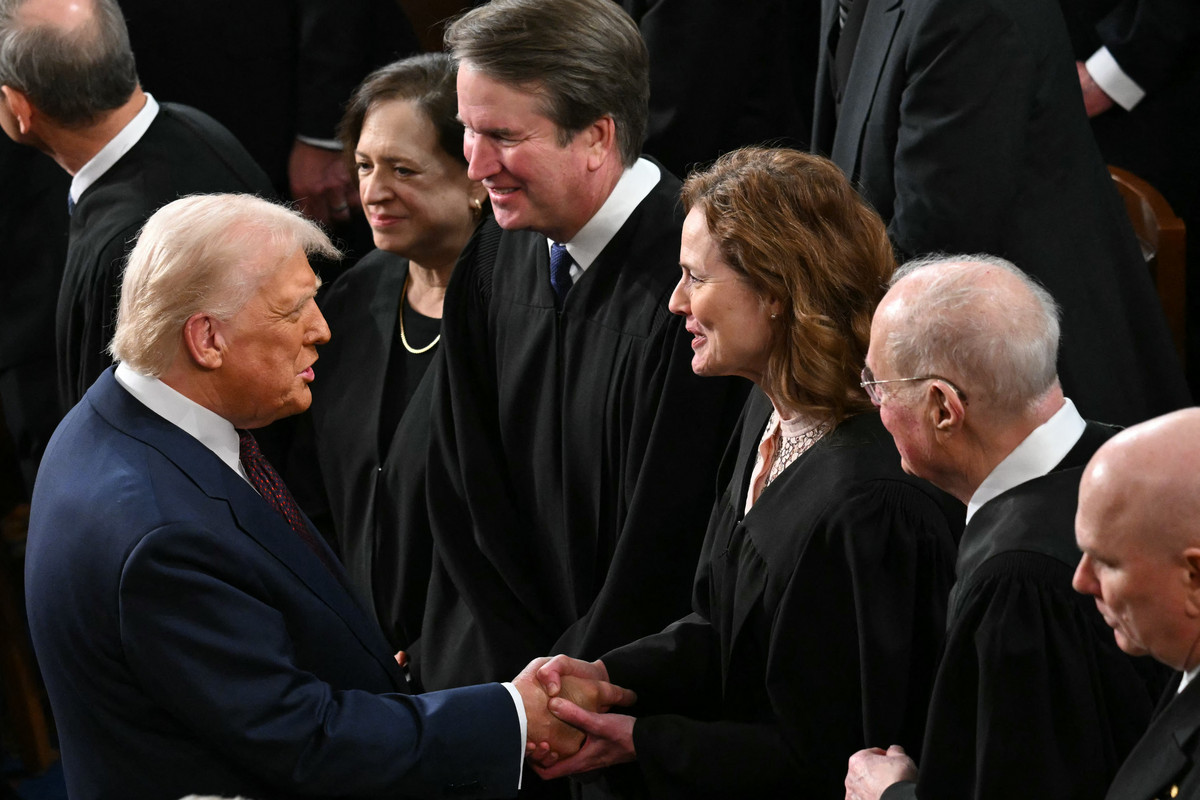

It all prompted Trump to call for Boasberg’s impeachment, which in turn evoked a rare public statement from Chief Justice John Roberts, who said impeachment is “not an appropriate response to disagreement” over court decisions.

Boasberg has since accused the Trump administration of willfully violating his ruling and moved toward contempt charges. An appeals court halted the proceedings for months, but they sprung back to life in November — until Trump sought to block them again last month by booting Boasberg from the case. A panel of D.C. Circuit judges is weighing next steps.

Despite being chief judge, Boasberg doesn’t control which judges are assigned to each case; the process is typically randomized.

Boasberg also oversees contentious legal fights like the lawsuit that followed “Signalgate,” when top administration officials’ war-planning group chat was allegedly leaked to The Atlantic’s top editor, and Rep. Eric Swalwell’s (D-Calif.) lawsuit against the Federal Housing Finance Agency over its criminal referral against him.

The battles have elevated Boasberg’s profile; there are T-shirts and stickers that call for his impeachment, while others call for him to be president.

Other D.C. federal judges — like Beryl Howell, the district’s former chief judge, and Ana Reyes — have faced misconduct complaints and demands to step aside from the administration.

In Maryland, Xinis was thrust into Trump’s immigration crackdown after she drew the case of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who was wrongfully deported to El Salvador in March in violation of a 2019 court order barring his deportation over safety concerns.

Xinis ordered immigration officials last month to immediately release Abrego Garcia and has barred his deportation for now. Her decision on the next steps in Abrego Garcia’s case is pending further briefing.

The Obama-appointed judge has signaled increasing frustration as the government has repeatedly resisted her orders.

In April, after she ordered the government to return Abrego Garcia to the U.S., Trump aide Stephen Miller claimed Xinis was effectively suggesting the U.S. should “kidnap a citizen of El Salvador and fly him back here.” Other officials criticized her as an activist judge, while putting off Abrego Garcia’s return.

Xinis said at a Dec. 22 hearing she was “growing beyond impatient” with the government’s repeated misrepresentations, questioning whether Abrego Garcia’s illegal deportation in the first instance undercuts any notion federal officials can be trusted not to do it again.

“Why should I give the respondents the benefit of the doubt?” she asked.

Xinis is not the only judge in her courthouse stuck in Trump’s crossfire on immigration.

The administration sued all 15 federal district judges in Maryland in June over the federal court’s standing order slowing down speedy deportation efforts, a striking escalation in its war with the judiciary. Though the lawsuit was thrown out, the administration has appealed; its opening brief is due later this month.

Federal judges have not all sat silently as the administration’s attacks on the judiciary have escalated. Some judges have anonymously spoken out in the press — or, rarer, publicly — to confront the assaults on their work’s integrity, especially as threats rise.

In fiscal 2025, there were 564 threats against judges, according to U.S. Marshals Service data. Since fiscal 2026 began in October, there have already been 131 threats.

Judges handling prominent cases involving the Trump administration say they’ve seen threats become even more prevalent.

U.S. District Judges John McConnell Jr. of the District of Rhode Island and John Coughenour of the Western District of Washington remarked at a virtual event earlier this year that harassment campaigns followed their assignments to major cases involving the president’s priorities.

McConnell in January 2025 blocked the administration’s federal aid freeze and said at the July event that his court had received more than 400 “vile, threatening, horrible” voicemails since then — including one wishing for his imprisonment and assassination.

He’s since overseen challenges to the Trump administration’s bid to block full Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits during the government shutdown and efforts to withhold millions of dollars in Federal Emergency Management Agency grants from Democratic-led states.

Coughenour, who indefinitely blocked Trump’s executive order to restrict birthright citizenship in February, recalled being swatted at his home and his family members facing threats.

“It’s just been stunning to me how much damage has been done to the reputation of our judiciary because some political actors think that they can gain some advantage by attacking the independence of the judiciary and threatening the rule of law,” the judge said.

U.S. District Judge William Young, who sits on the federal bench in Massachusetts, topped a major ruling finding Trump’s crackdown on pro-Palestinian campus activists unlawful with an anonymous threat he received that read, “Trump has pardons and tanks … what do you have?”

The judge responded in the ruling that, alone, he has “nothing but my sense of duty,” but together, “We the People of the United States — you and me — have our magnificent Constitution.”

Young’s ruling took specific aim at Trump, pegging him as a bully prone to “hollow bragging” and pointing to his “retribution” against law firms, higher education and media as proof of the president’s “problem” with the First Amendment.

An earlier ruling from Young drew the Supreme Court’s justices into the judiciary’s fight with Trump.

After Young blocked Trump from cancelling hundreds of millions of dollars in National Institutes of Health grants linked to diversity initiatives, the Supreme Court reversed, making way for the cuts.

Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, accused the district judge of seeking to “defy” an earlier emergency ruling the high court made in another grant cancellation case.

Young apologized from the bench, after which retired Justice Stephen Breyer gave a rare interview to The New York Times rejecting the notion that Young, whose rulings he reviewed as an appeals judge for years, would ever “deliberately defy” the justices. Roberts remained mum.

In rare interviews with NBC News, a dozen anonymous sitting judges appointed by Democratic and Republican presidents alike criticized the Supreme Court and Roberts for doing little to defend the integrity of their work against Trump and his allies’ attacks, as violent threats rise.

The chief justice’s end-of-year report on the federal judiciary made little mention of the judges’ frustrations.

In the penultimate paragraph of a review more centered on history than current affairs, Roberts suggested looking to former President Coolidge’s words for guidance on a path forward.

The nation’s 30th president urged Americans to turn to the Declaration of Independence and Constitution for “solace and consolation” amid “all the clash of conflicting interests” and the “welter of partisan politics.”

“True then; true now,” Roberts concluded.