GROVE HILL, Ala. — One of the last remaining birthing units in southern Alabama will close next month to qualify for federal funding that will save the hospital’s emergency services, but doctors warn the move may cost newborns and pregnant women essential access to obstetric care.

Nestled in rural Clarke County, the small, nonprofit Grove Hill Memorial Hospital will discontinue its labor and delivery services in mid-August, the governing board announced earlier this month.

The board said closure was necessary for the hospital to qualify for much needed federal funding that is designated for rural emergency hospitals, defined as facilities with fewer than 50 beds that provide 24/7 emergency care and no inpatient services, including obstetric

But the federal funding comes at a steep cost. The closure marks the fourth labor and delivery unit to close statewide in less than a year, including a facility in a neighboring county that referred many patients to Grove Hill after closing in November.

In the coming months, a large part of southern Alabama will no longer have close access to hospital obstetric delivery services.

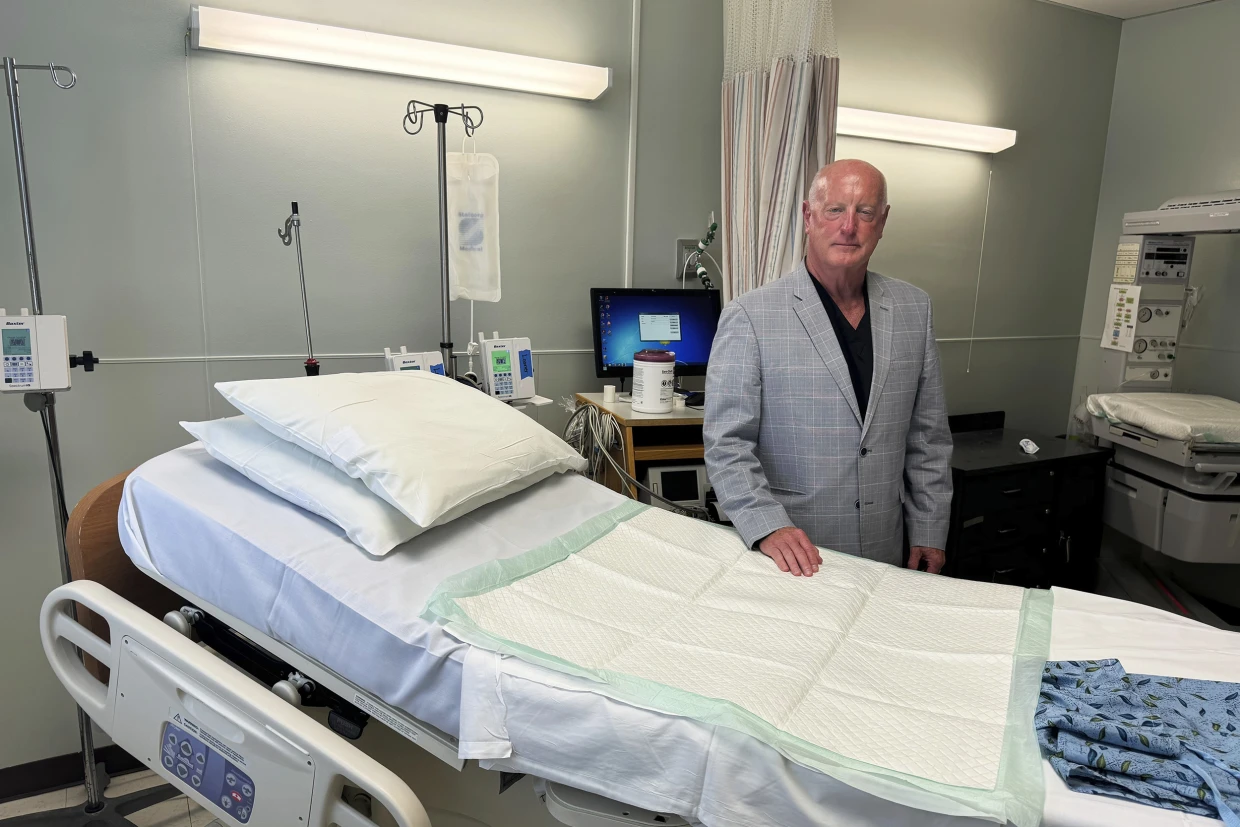

Dr. Max Rogers, the obstetrician-gynecologist who runs the labor and delivery unit at Grove Hill Memorial, sees an average of 300 women a month and delivers 10 to 15 babies. Rogers said the lack of local care could put some mothers and babies at risk.

“I used to say that outcomes are gonna be worse,” Rogers said. “And that’s a nice, polite euphemism for babies are going to die and mothers are going to die in emergency rooms because of a lack of prenatal care and a lack of obstetrical care.”

This would apply to a small but significant fraction of births involving serious complications. Although emergency rooms are equipped to handle the vast majority of normal births, some conditions require rapid transportation to a facility with a doctor qualified to operate on pregnant women, Rogers said.

Anna Retic, 26, has been driving 45 minutes from her home near Pine Hill to Grove Hill for all seven months of her pregnancy because it was the closest facility offering both birthing and prenatal services.

She considered herself lucky. She works as a bank teller and is able to take time off to make the trip to her monthly appointments, which were scheduled to increase to once every two weeks as her October delivery date gets closer.

Now, the closest option for her to give birth is a hospital almost twice as far away.

“It’s crazy,” Retic said. “If you’re in labor, you have to rush two hours away, you might have that baby in the car. I don’t know. I pray that doesn’t happen to me.”

Alabama’s delivery health outcomes already lag far behind the rest of the country. One study found Alabama had a maternal mortality rate of 64.63 deaths per 100,000 births between 2018 and 2021, nearly double the national rate of 34.09 per 100,000 births. That jumps to 100.07 deaths for Black women in the state.

Rural hospitals have struggled to maintain labor and delivery units for decades. Experts cite declining births, low Medicaid reimbursement and staffing shortages as significant causes of financial decline.

But some of the strain is more particular to Alabama, which is one of 10 states nationally that has not expanded Medicaid.

Dr. Donald Williamson, president of the Alabama Health Association, said a major challenge for rural hospitals in the region is a significant number of patients that come through the front door are uninsured.

The expansion of Medicaid would improve reimbursements and hospital revenue, Williamson said, and until then he expects more hospitals across the state to make the same difficult decision made at Grove Hill.

Nationwide, 28 hospitals have converted to the rural emergency designation since the program was rolled out in 2023, according to the University of North Carolina’s Sheps Center for Health Services Research. But Grove Hill will be the first that will have to close a labor and delivery unit to become a rural emergency hospital, according to the National Rural Health Association.

While the program has offered a unique lifeline to rural hospitals on the brink of collapse, experts and legislators have warned it might come at the cost of essential services like inpatient psychiatric or other rehabilitative care.

U.S. Senators Jerry Moran, a Republican from Kansas, and Tina Smith, a Democrat from Minnesota, introduced legislation in May to allow rural emergency hospitals to maintain some inpatient services, including obstetrics.

Ultimately, Rogers in Grove Hill said he supports the conversion to a rural emergency hospital, even if the change means closing the obstetrics department where he has formed close relationships with many patients. He believes it is the hospital’s only financial option and important in maintaining emergency services.

Still, Rogers has significant concerns about the future of the federal program.

“Every single one of us needs to understand that while this REH status may protect a lot of rural hospitals, it’s coming with a price. And that’s what I don’t want everybody to gloss over,” he said.