In case you haven’t heard, President Joe Biden’s had a rough two weeks.

After a debate performance that launched waves of Democratic panic, finger-pointing and intrigue about whether to make a late-cycle switch at the top of the ticket, many onlookers have latched onto a handful of since-released polls for insight into the situation.

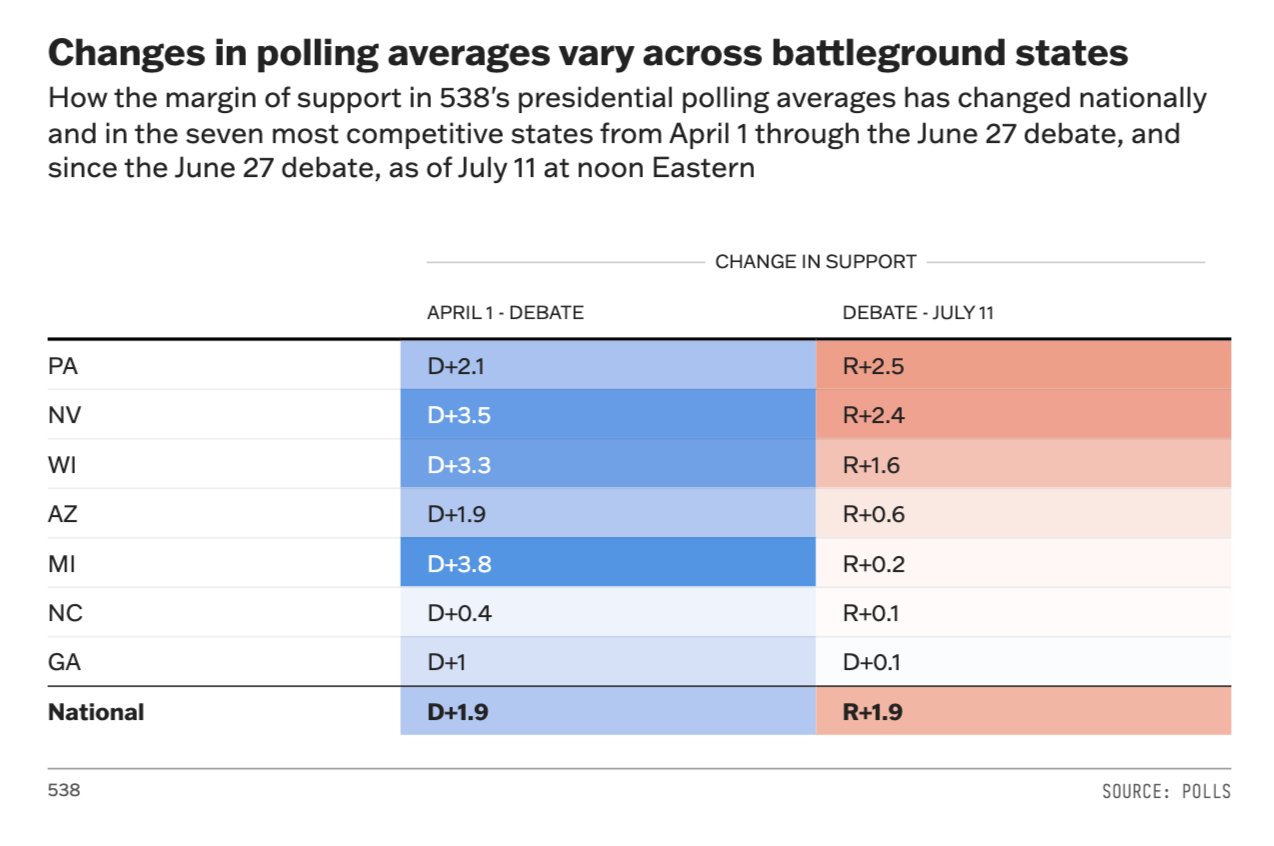

538’s average of the presidential race includes a few dozen polls fielded entirely after the June 27 debate. Most show a modest gain for former President Donald Trump over Biden, and the average has correspondingly increased from about a dead heat on debate day to a lead of around two points for Trump as of July 11 at noon Eastern.

Observers and operatives, as they are wont to do, have made hay of this.

To hear some tell it, Biden’s campaign is on the verge, its time and place of death roughly 9:20 p.m. on June 27 in Atlanta. In the months leading up to the debate, polls showed Biden trailing in most battleground states. And while the president showed some signs of gaining ground just ahead of the debate, most observers agreed that he took the stage needing to notch a win, particularly to reframe concerns about his age.

Instead, he did the opposite, turning in a performance filled with verbal stumbles that put his age on full display to tens of millions of viewers and launched a feeding frenzy as a growing number of concerned watchers, commentators and now Democratic electeds have called for him to bow out of the race.

Listening to others — including the Biden campaign — the drop really isn’t so steep. They’ve mostly characterized the post-debate polling dip as marginal, something that the president has plenty of time to put in the rearview mirror. And in such a high-polarization, high-information race — voters know just about everything they possibly could about these two candidates, Biden’s age concerns included — there just isn’t much room for the needle to move.

Both of these accounts have merit, of course, but any post-debate analysis using polling to justify sweeping conclusions about the state of the race is way out ahead of the data. This soon after the debate, with relatively few polls having come home to roost, there are early indications that Biden has lost at least a point or two in the polls, but the early indications are just that — early indications. (This is why, as G. Elliott Morris explains here, 538’s forecast hasn’t changed much post-debate.)

Here are four reasons to be wary of the post-debate polling takes:

It takes time for polling to reliably register shifts in public opinion.

“The whole premise around election polling, and the reason that we do it over and over and over again before the election, is that people’s opinions change,” said Cameron McPhee, the chief methodologist for SSRS, a nonpartisan pollster that works with CNN, among others, on election polling.

Polling is by nature tricky and imprecise; it’s exceptionally difficult to estimate how an entire country will vote from a sample of perhaps 1,000 respondents. Because any one poll could be distorted by statistical noise, it takes lots of data points — and thus lots of time — to get the true pulse of public opinion and distinguish which measures may be outliers (in McPhee’s language, to distinguish the “signal” from the “noise”).

That brings us to the first time-based issue with the post-debate polling: While it may not feel like it, we just don’t have that many data points yet, and the polls we do have differ greatly in method and quality, complicating like-to-like comparisons.

For example, we can see that there’s quite a bit of variation among even the highest-quality post-debate polls. Since June 27, five pollsters with a 538 pollster rating of at least 2.5 out of 3 stars have conducted surveys asking voters which presidential candidate they favored: YouGov, The New York Times/Siena College, Suffolk University, Emerson College and Ipsos. (YouGov conducted three surveys among registered voters with two different news outlets.) The results range from a Trump lead of between 1 and 7 percentage points:

To get a sense of how much polls have shifted since the debate, we can also look at how the results of these polls compare to the most recent conducted by the same pollsters before June 27:

As you can see, the size of these shifts isn’t that large, at least relative to some of the doom-and-gloom prognostication about the total collapse of Biden’s campaign.

Lest you conclude that these modest shifts in polling mean the debate just wasn’t that impactful, consider a second time-related problem: While it may seem out-of-step with your experience — many of you readers, like me, probably refresh your news feeds constantly! — the vast majority of Americans receive political information more slowly, hearing about the news through a mix of traditional media, social media and their personal networks. That means that broader public opinion often lags behind big events, as well as the dizzyingly fast news cycles that follow them.

Low(er)-information voters learn about politics through what’s called “incidental exposure,” according to Erik Nisbet, a professor of media and public opinion at Northwestern University.

“They’re exposed to news information by accident, in a sense,” Nisbet said. “It would take some time, with a big event like this, through their interpersonal networks or their online networks, to be exposed to it.”

This is especially so for a debate with unusually low viewership. The first debate drew over 30 million fewer viewers than its equivalent in 2016, likely due in part to a streaming-induced decline in TV viewership and in part because it was held historically early in the election cycle, at a time when many Americans are more focused on summer vacation than the November election.

We can also assume that the group of voters who didn’t watch the debate are less politically informed and, relatedly, less firm in their candidate preference than those who did, making them likelier to be persuaded by new information. In other words, the group of non-debate-watchers is larger, more swingy, and thus likeliest to move the polls, but it’s also probably the slowest to receive information about big events.

Polls taken in the week immediately following the debate (including most of the high-quality polls we have so far), then, may not reflect the full effects of the debate — or the steady drip of negative news about Biden in its aftermath.

At the risk of getting a little bit meta, this means that media coverage of polling can be something of a self-fulfilling prophecy: If everyone says a candidate is tanking after a bad poll or two, it can drag them down even further. Two weeks out, the post-debate news cycle is certainly still in full swing, so, as McPhee put it, “The media has great power right now in this post-debate world.”

“How these polls are reported isn’t happening in a vacuum,” she added. “It is going to drive the election.”

Six or seven of the country’s most competitive states will likely decide the outcome of the election, but there’s been very little polling in each of those states since the debate. Even as the count of national polls since the debate ticks up, it’s important to keep in mind that the number of battleground-state polls will almost always lag behind.

As it stands, the number of post-debate polls included in 538’s state polling averages for each of seven core swing states ranges from one to five, with at most two from a 538 pollster rated at least 2.5 out of 3 stars.

To the extent that national polling is strongly predictive of battleground-state polling, this wouldn’t be the biggest deal. And while we should be cautious about reading too far into limited state-level data, a look at 538’s polling averages in seven battleground states before and after the debate shows that polling shifts at the national and state levels don’t necessarily move in tandem.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that the average voter in each of the battleground states may behave differently than the average voter nationally. Beyond basic demographic differences — Arizona has a far larger Hispanic population than the country as a whole, for example, while more Wisconsinites work in manufacturing — voters in swing states also find themselves bombarded by focused efforts to sway their votes from both sides, which could significantly alter the post-debate effect.

An NPR analysis in late May found that more than 70 percent of ad spending since March had been in the key battleground states, and the Biden campaign recently announced $50 million in ad spending there in the month of July alone, including several spots hitting Trump for his comments in the debate.

Faced with this onslaught on the airwaves and a steady cadence of in-person appearances by the candidates and their surrogates, swing-state voters may form impressions of the debate differently from the rest of the country.

There’s no shortage of polling-driven takes on the debate, but many are performing a one-dimensional analysis on (at least) a two-dimensional problem. That’s because a heavy focus on candidate preference polling tends to gloss over another key component: turnout.

No matter how much you engage with polling, odds are you’re used to hearing about changes in candidate preference — a two-point gain for Trump, or a one-point drop for Biden. But at least as essential a consideration as who folks plan to vote for is whether they will vote at all. Consider this: A candidate trailing her opponent by two points in a head-to-head poll would win comfortably if five percent more of her supporters turned out on Election Day.

“I think we focus too much on persuasion when it comes to campaigns, when it comes to debates, especially in this election,” Nisbet said. “It’s so polarized. These are very established candidates. … So really, it’s about turning out the bases and the leaners.”

McPhee agreed that turnout should be a bigger focus when it comes to how major events like debates affect voting behavior. Lower-propensity voters are “going to be the group that sways the election one way or another,” she said. “That’s probably the group that is most impacted by these big performances.”

We can assume that most of these lower-propensity voters are already leaning toward one candidate or the other, so the debate may not have changed their candidate preference. But it’s not a big leap to imagine that Biden’s poor performance could hurt his supporters’ enthusiasm — or energize Trump-leaning voters to turn out against him. In this respect, any analysis focused solely on shifts in preference may be underestimating the extent of the damage for Biden.

Such preference-only analyses don’t just result from an obsession with the political horse race, though — turnout is also much harder to reliably predict than candidate preference.

In recent years, pollsters have faced major questions about how to effectively collect responses and weight their polls to ensure a representative sample of voters likely to head to the polls in the fall. These problems are all the more difficult to overcome four months before an election. McPhee noted that reputable pollsters doubt that respondents can accurately predict whether they will show up to vote several months hence, so many polls at this stage in an election cycle sample registered rather than “likely” voters. (McPhee told me that SRSS, for example, will probably not make the switch until August.)

This means that we do not — and perhaps cannot, at this point in the cycle — have a good read on how much this debate shifted the universe of likely voters, though it will matter at least as much as candidate preference come November.