Lucious Abrams is the third generation to take over the family Georgia farm, an operation that has long grown cotton, corn, and soybeans. When he did not receive a loan in time to buy the seeds and supplies he needed, he joined the Pigford v. Glickman class action lawsuit against the USDA.

The 1999 lawsuit alleged that in myriad ways the agency discriminated against Black farmers resulting in uneven distribution of farm loans and assistance. This caused many Black farmers to lose their land and farms to foreclosure.

Pigford plaintiffs, like Abrams, were supposed to receive payments after the case was settled in 1999. However, tens of thousands missed out due to confusing paperwork and filing deadlines and what neared attorney malpractice, advocates say.

In 2010, Congress appropriated an additional $1.2 billion in a second round of payouts. But still, many did not receive them due to more denials of claims and deadline and processing issues.

But in addition, many say there has to be a larger culture shift at the department because farmers do not trust their loan applications will be processed fairly — if they can even file.

Indeed, an NPR analysis of USDA data found that Black farmers receive a disproportionately low share of direct loans given to farmers leaving them behind in a program that is important to their livelihoods. The department itself has long tried to fix these systemic problems, but many farmers and advocates remain skeptical that its efforts will ultimately benefit those who need it most.

The USDA’s lending process, for the last century, is not set up to support nontraditional growers including the farmers of color who face high rejection and withdrawal rates as a result, said Zach Ducheneaux, the Farm Service Agency Administrator at USDA.

“So it might be you’re a Black farmer that’s operating on heirship property who hasn’t had the benefit of a cooperator technical assistance provider right there on the ground with them to help them navigate this,” Ducheneaux said of Black farmers who have owned land for generations but may not know how to navigate USDA’s processes. “By virtue of the lack of support structure around them, they’re going to come to the application process less prepared.”

Black farmers still receive the lowest amount of loans

In 2022, the department granted direct loans to only 36% of farmers who identified as Black, according to an NPR analysis of USDA data that looked at how many direct loan applications were accepted, rejected or withdrawn per each racial group. Direct loans are supposed to be among the easiest to get at USDA. They are meant for farmers who can’t get credit elsewhere and can be used to get land, farming equipment or other operational costs needed to keep the business afloat.

In contrast, 72% of white farmers who applied were approved. Perhaps some of the biggest gaps in the loan demographics can also be seen in the rejection numbers, where 16% of Black farmers were rejected — the highest amount; the corresponding figure for white farmers was 4%. And 48% of Black farmers withdrew their applications, also the highest amount tied with Asian farmers and compared to 24% of white-identifying applicants.

By and large, across the first two years of the Biden administration, Black and Asian-identifying farmers were the least successful in acquiring a direct loan, data shows.

And it is not just about direct loans. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack has long made the point that farmers of color received less than 1% of coronavirus pandemic farming aid, despite making up 5% of all farmers.

The denials and withdrawals are high

Advocates for farmers of color have argued that rejections and withdrawals often happen because the multi-step application process is too cumbersome and confusing. Those whose families have generational experience and long-standing outside resources to navigate the federal bureaucracy sail through.

Hmong farmers in Minnesota, for example, may often lease land but they are not given a written contract that they need to qualify for loans, said Janssen Hang, executive director and co-founder of the Hmong American Farmers Association.

Farmers keep records and file taxes, but not in a way suitable for the Farm Service Agency, USDA’s lending branch. And it’s all complicated by the lack of bilingual federal employees, documents and training materials.

In some cases, language barriers are a major issue, including for Hmong American farmers and Hispanic farmers.

“They can enroll in a farm business management course, but it’s all conducted in English. And this particular constituency here does not read, read or write English fluently or understand, so they can sign up for the farm business course, pay $2,000 a year just for this course here and what did they walk out with? Stress,” Janssen said. “They walk out without any adequate information to really enhance or fund operations here because it is done in a language that they’re not familiar with.”

Farmers are also often denied for having low or no credit, despite USDA being considered the “lender of last resort” for producers who cannot get credit elsewhere.

The way people are farming is also changing. Urban farms, farms with multiple crops, hemp farms, and others also challenge the loan system which was originally designed for large, one-crop farms.

The USDA is seeking to address the issue

Advocates argued that Vilsack did not do enough to help provide equity and fairness to USDA loan processes during his first term as agriculture secretary under Obama. A 2019 investigation by The Counter found that the department distorted data on Black farmers to paint a rosier picture.

The Biden administration vowed to fix the department’s history, starting with the appointments.

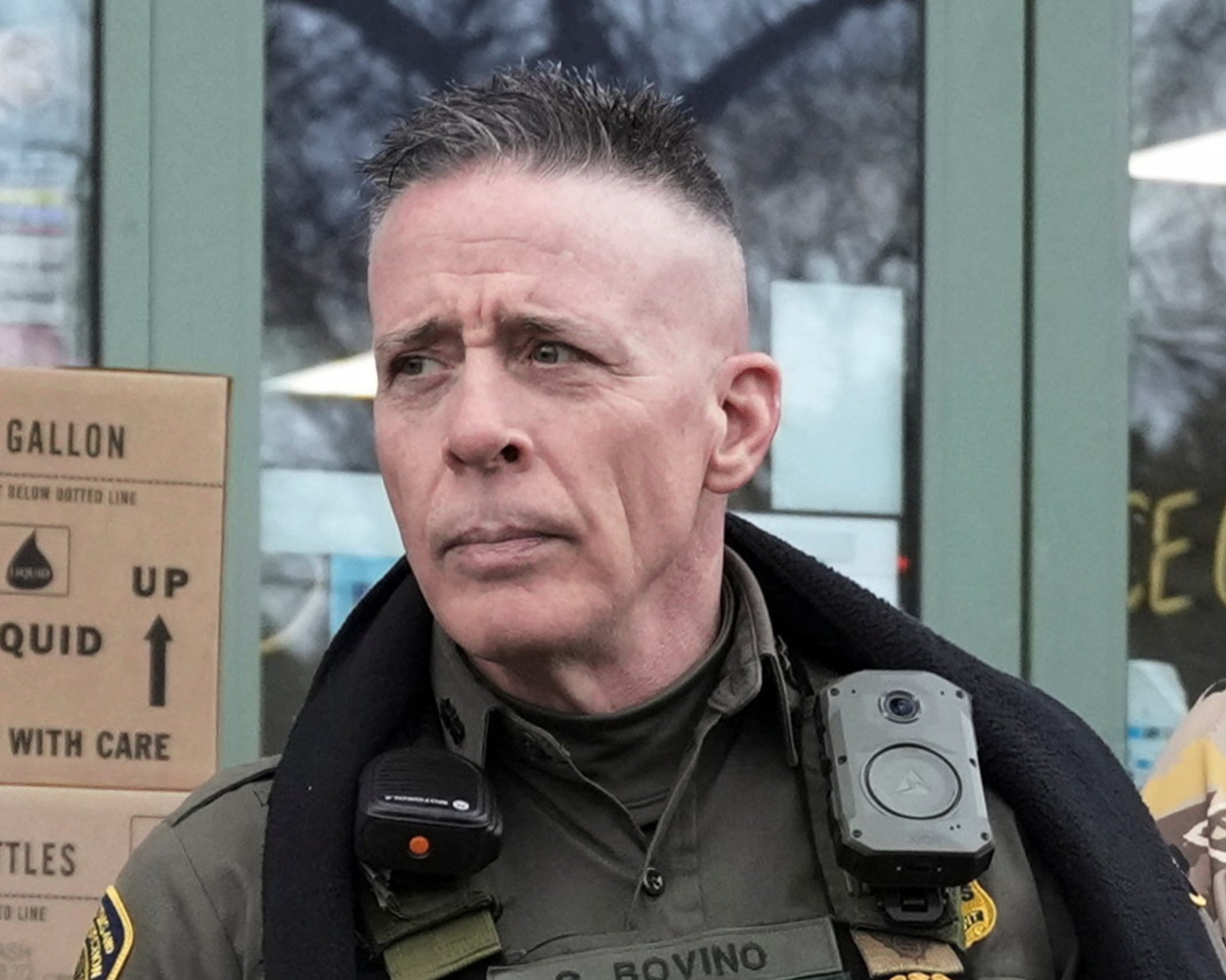

The Farm Service Agency is led by Ducheneaux, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe and the first Native American in the role. Prior to being at the department, he served as the executive director of the Intertribal Agriculture Council, an advocacy group for Native American farmers. Indigenous farmers were also a part of their own lawsuit alleging discrimination against USDA and they have long been left out of programs despite having high direct loan acceptance rates.

“I take that very personally because I’ve been trying to get them in the door since way before I got here,” Ducheneaux said regarding barriers to access to the department that spans across race groups. “My personal goal is to get all of these to as close to 100% as we can.”

He credits lessons learned in Indian Country for some of the department’s solutions including working closer with cooperative groups. Using agreements with organizations on the ground that represent different producers, USDA is trying to work through them to get information to farmers.

“We see this as a chance to leverage the trust that we don’t have in these communities. In many cases, rightfully so,” Ducheneaux said. Agreements spread across young and veteran farmer groups, Hmong American Farmers Association, the Intertribal Agriculture Council and the Federation of Southern Cooperatives.

As a result of the agreements, these organizations report being able to increase staff, expand outreach, and increase their ability to give feedback to USDA.

“Step one of rebuilding trust is acknowledging the fact that we have treated people poorly in the past, and discriminated in the past, and still have practices that feel like active discrimination today,” he said. “There is that inherent, intrinsic trust in that NGO or that nonprofit that probably in our lifetime, we’re never going to rebuild it at the agency or department level. So we’ve got to start somewhere, and that’s a great place to begin.”

In order to reduce the paperwork, speed up decisions and get payments out the department announced this month its plan to shorten the applications from 29 pages to 13.

Last year, the department also launched an online program to help producers understand which loans they may qualify for in an effort to reduce the rates of denials and withdrawals. A separate USDA Equity Commission, born out of a Biden executive order calls for federal departments to address racial equity and underserved communities.

The group met earlier this month to vote on over 30 recommendations ranging from reducing the number of years of experience needed to participate in conservation programs to making the language in FSA loans more accessible – actions they believe the department can get a head start on. A final report is due by the end of the year.

Meanwhile, farmers say they need help and change now.

Black farmers are looking for debt relief

Black farmers who should have gotten relief from Pigford say not all the settlements made it into their hands.

And as time passed, interest, delinquent payments and more stacked up against their businesses.

“We haven’t gotten any relief as far as these lawsuits or debt relief, and that will impact me severely,” said Rod Bradshaw, a farmer in Kansas, adding that the rising costs of fuel and production are thinning his margins.

As a part of the Inflation Reduction Act, the Democrat-led spending bill, members slipped in a provision that created a $3.1 billion debt relief program for “economically distressed borrowers.”

According to Ducheneaux, the department completed automatic payments towards about 11,000 distressed borrowers who were 60 days or more delinquent on direct and guaranteed USDA loans as of Sept. 30 of last year. USDA data analyzed by NPR shows over 13,000 producers have received a payment on their accounts as of Jan. 30.

These payments, however, are to all “distressed farmers,” including some white farmers. They may not include all Black farmers. The race-neutral program is an alternative to a lawsuit-blocked race-targeted program first passed by Congress.

The bill did include $2.2 billion to the department for farmers who have specifically faced discrimination in USDA lending programs. This money is mandated by Congress to be disbursed by third parties or nongovernmental organizations.

“We have to be open-minded enough to see if there are some solutions that can be brought to the table that help address some of those cumulative impacts of prior discrimination,” said Dewayne Goldmon, the first Senior Advisor for Racial Equity to the Secretary of Agriculture at USDA. “That has to be an important part of the process.”

In October, the USDA launched a request for information to gather public comments on how to create and implement the program. The comment period closed in November and the department is currently reviewing those submitted.

“I would consider [the efforts] successful when my position is no longer needed. When you don’t need an adviser for racial equity,” Goldmon said. “And I’m not being naive, but I have to keep that as a goal.”

Npr

Tags: Black farmers