The Trump administration is turning up the pressure on schools to rein in student loan default rates ahead of changes the federal government is implementing this summer that advocates worry could hurt borrowers.

The Department of Education released guidance to universities this week to offer “best practices to reduce default rates” — and reminded schools that failing to meet their obligations could lead to a loss of access to federal student aid programs.

The guidance offered some transparency experts say will be useful for institutions, but it also fueled concerns the Trump administration is seeking to pin blame on universities for the high default rates after curtailing debt relief efforts.

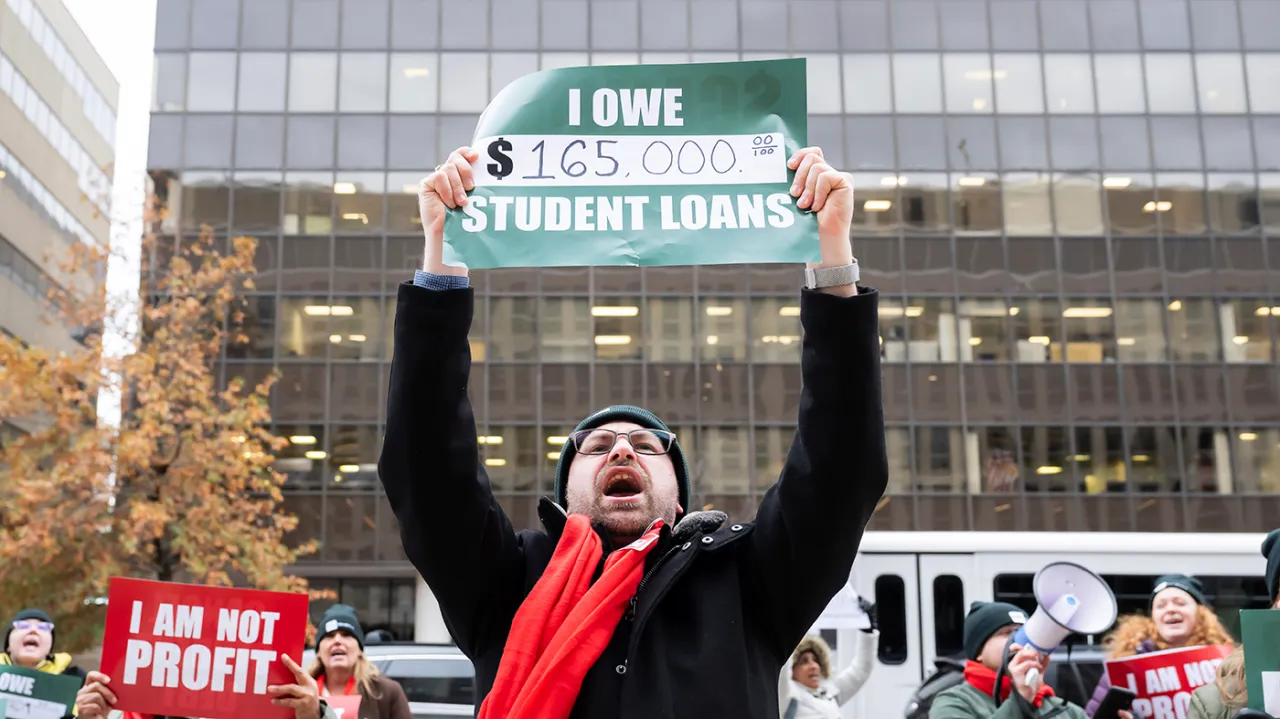

An analysis by the Congressional Research Service last year showed more than 5 million student loan borrowers were in default and millions more were close to that threshold. A borrower is considered to have defaulted on their student loans after 270 days without a payment, leading to damage to their credit score and even potential wage garnishment.

“We know that schools are seen by their students as so-called trusted voices or trusted agents. And again, historically, we have found that the messaging can be more effective coming from a school than maybe coming from a loan servicer,” said Betsy Mayotte, president and founder of the Institute of Student Loan Advisors.

The Education Department said universities with a cohort default rate of more than 30 percent for each of the three most recent fiscal years could jeopardize its access to the Direct Loan program. A school is also at risk of losing access to the program if its most recent fiscal year default rate is above 40 percent.

The cohort default rate measures how many borrowers went into default within three years of entering repayment. It is different from the nonpayment rate, which measures how many borrowers who have entered repayment since January 2020 were more than 90 days delinquent on payments when data was collected in May 2025.

The department, which said nonpayment rates can be an early indication that a school’s default rates is likely to increase, found 1,800 schools have nonrepayment rates at or above 25 percent.

“With nonpayment rates rising at hundreds of colleges and universities across the country, institutions must do more to support successful loan repayment outcomes,” said Under Secretary of Education Nicholas Kent.

“Student borrowers have an obligation to repay their loans, but institutions also share a responsibility to ensure their students are prepared to enter repayment and understand the consequences of nonpayment. Institutions cannot benefit from taxpayer dollars while ignoring the fact that a significant share of their students are not well-prepared to repay their loans. It’s time for institutions to step up or risk losing access to federal student aid,” he added.

While experts agree on the importance of colleges supporting students after they leave and giving them information regarding loans, they worry the guidance paints an unfair picture regarding schools’ responsibility on the issue.

The department “is trying to draw a correlation between non-repayment rates and that being the fault, the direct fault, of the institution of higher education,” said Emmanuel Guillory, senior director of government relations at the American Council on Education. “Now, when it comes to ensuring that borrowers are repaying when they graduate, they have a direct relationship with their lender, and it is through the lender in that direct relationship that they establish their repayment plan.”

Reached for comment, the Education Department said, “Institutions are charged with delivering high-value credentials to students — and many graduates are walking away with debt they cannot repay.”

“It’s time for institutions to acknowledge whether their services are truly preparing students for the workforce, and help both current and past students responsibly manage the debt they helped saddle them with,” said agency press secretary Ellen Keast.

Meanwhile, big changes are coming to the student loan system.

This summer, the Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP), created by GOP legislation last year, will become the only income-drive repayment (IDR) plan available to future borrowers. The plan will adjust payments based on a person’s income.

The only other option will be the standard plan, which bases payments on the size of the loan, with timelines ranging from 10 years to 25 years.

Advocates worry default rates will go up as these plans do not offer as much flexibility as the repayment options currently available.

“Our concern with the plans are, of course, on affordability of them, and so that is the biggest challenge, how they’re going to affect students who have to make higher monthly payments … a small cost of living raise can really drastically affect how much someone can be forced to repay under the RAP plan. So, those are the types of things that could easily cause students to miss payments and then go into non-repayment and potentially go into default,” said Christopher Madaio, senior advisor of accountability at the Institute for College Access & Success.

And while experts higher education could be more proactive, there are worries that universities will not offer the best solutions to students.

“There’s different payment situations students can be in, right? And what we don’t want to see happen is something called forbearance steering, which is where students, because it’s easier for the school or for their contractor, to get a student into forbearance,” Madaio said.

“We have seen examples in the past of servicers and, even institutions, just getting students into forbearance, even though that wasn’t the best thing for the student,” he added. “That’s a temporary Band-Aid that can make schools’ non-repayment and default rates appear better than they are, but it actually can harm students in the long run.”