Availability of manuals and instructions on less moderated apps and forums is making extremist content accessible.

A spate of recent vigilante and extremist attacks in the US have highlighted how the booming availability of internet resources is a growing national security concern.

Experts and world governments have been sounding the alarm on digital radicalization as accessibility to materials such as assassination manuals, files for 3D printed guns, or something as simple as ChatGPT grows.

During the early days of the war on terror, obtaining literature and guidance on lone actor terrorist attacks from an organization like al-Qaida could require more obscure dark web access or specific tradecraft from harder to reach parts of the internet.

But in 2025, on apps such as Telegram or Discord, which are downloadable and have limited barriers for entry, extremists and militant organizations of all political ideologies are regularly sharing PDFs or archives of military and insurgency skills primed for do-it-yourself terrorism.

While the democratization of technology has enabled a surge in the access to information, it’s also proliferated tools for acts of public violence.

Luigi Mangione, the alleged killer of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, is believed to have used a 3D printed pistol in the killing – the file for it downloaded online.

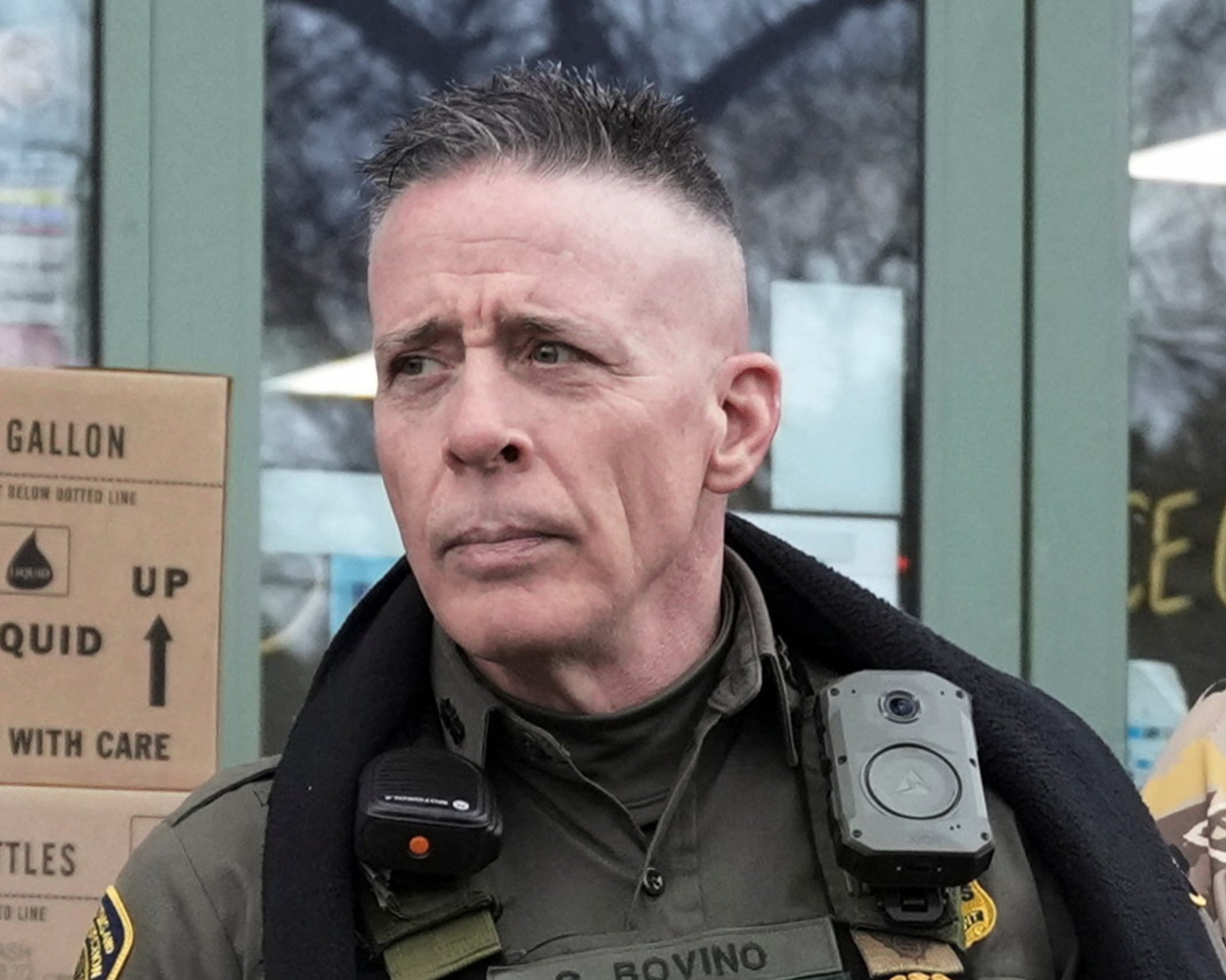

The IS-inspired New Orleans attacker on New Year’s Day executed a textbook car ramming – the exact kind the terrorist organization had been calling for in magazines published and re-shared for years. Even the Cybertruck bomber in Las Vegas used the help of generative AI and ChatGPT to plan his attack, something Kevin McMahill, sheriff of the Las Vegas metropolitan police department, called a “game-changer”.

Some of the most secretive and powerful sections of global security agencies have also taken notice.

The 5-Eyes, an intelligence sharing alliance between the spy and law enforcement agencies of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the US released a joint report at the end of 2024 raising concerns about online extremist content and youth radicalization.

“Violent extremist content is more accessible, more digestible and more impactful than ever before,” said the report. “Violent extremist individuals and groups share material which individuals often consume as part of their radicalisation process.”

The same report made it clear that the broadening availability of extremist content on more mainstream apps has enabled “the spread of grievances and narratives which promote violence, a process which can take place entirely online”.

“The Director General of MI5, Ken McCallum, has recently highlighted how counterterrorism now competes with other national security priorities for resources,” said Adam Hadley, the founder and executive director of Tech Against Terrorism, an online counterterrorism watchdog, which is supported by the United Nations Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate (CTED).

“This comes at a particularly concerning time, as we’re witnessing an upward trend in radicalisation and terrorist activity related to the internet, following several years of reduced counterterrorism resourcing across western governments.”

Hadley continued: “Of grave concern is the trending debate around content moderation, particularly emanating from the United States.”

On Tuesday, Mark Zuckerberg, the Meta CEO, announced that his company would drastically reduce content moderation in the vein of Elon Musk’s X. Many critics now wonder how much terrorist content will be allowed to proliferate on their platforms.

It all represents an increasingly difficult task facing western governments trying to thwart terrorism inside their own borders. In the past, users on specific and known sites could be surveilled or intercepted when they approached an operative of a terrorist group; now, highly specific terrorist manuals in the hands of many gives an advantage to someone intent on being an undetected lone actor.

For example, an entire chat room on RocketChat, the choice messaging app of IS supporters, is nicknamed the “kitchen” and provides interactive recipes for bombs someone can make using over-the-counter products from hardware stores.

“Easy to prepare dish from the kitchen,” said one of its posts with an instructional video on how to make a common explosive.

Notably, while IS said it did not direct the terrorist attack in New Orleans, it did claim that their online propaganda and content had inspired the attacker.

And these instructional terror guides are highly specific: everything from picking the target, to tailoring the best type of attack to that target, to the weapons and operational security to carry it out, are inside many of these digital resources.

It’s not only IS and other jihadist terror groups spreading these kinds of manuals. At its inception, neo-Nazi terror group the Base hosted an entire digital trove of documents on guerrilla warfare, US Marine training, interrogation tactics, counter-surveillance techniques, bomb making and chemical weapons creation.

More recently, Terrorgram, a proscribed white supremacist terrorist entity, seeded assassination lists across multiple platforms and frequently released guides outlining how to attack critical infrastructure, carry out mass shootings, bomb cell towers, derail trains and carry out broader hate crimes.

“Damaging railroads, the veins of the beast system, is no casual affair and is time/labor intensive,” said one of the Terrorgram guides obtained by the Guardian. “It would likely require a decent chunk of explosives.”

Cody Zoschak, a senior analyst at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, said he finds instructional manuals created by terrorist groups themselves the most concerning.

“Manuals related to firearms, espionage, explosives, hacking or other illegal activities are widely circulated in poorly moderated online spaces such as Telegram,” he said.

“The Terrorgram Collective, which has not published a magazine since 2022, was known for including fictional first-person narratives of infrastructure sabotage and terrorist attacks alongside detailed instructions.

“In these instances the instruction manuals, which are tailored to match the strategy and tactics of the groups producing them, not only provide guidance to would-be-attackers but may also help mobilize an already radicalized individual to violence.”