The old woman was missing her left thumb. A thick layer of dirt covered her arms and legs. And when the police officers and social workers got close, a foul smell filled their nostrils.

It was July 2018, and the authorities had showed up at the house in West Covina, California, after receiving reports that multiple people were living on the property for unknown reasons and cars were roaring in and out of the backyard at all hours of the day.

But the homeowner, LaDonna Davis, 74, wasn’t in any position to shed light on the situation. She seemed confused about who was staying there and what they were doing. At one point she fainted in front of the officers.

“We’ve got to get her out of here,” Gilbert Amis, an officer with the West Covina Police Department’s code enforcement division at the time, recalled thinking.

Amis knew LaDonna. Nearly everyone in West Covina knew LaDonna, or at least knew of her.

She and her husband, St. James, first made headlines in the late 1960s when they adopted a baby chimpanzee named Moe and raised him like a son.

But St. James had died the previous week and now the officers believed his frail and cognitively impaired wife was being taken advantage of.

They had no idea that it would take nearly a year to extricate her from the situation, and during that time hundreds of thousands of dollars would be drained from her accounts, most of her possessions would be stolen and members of a violent motorcycle gang would take control of her property.

“We couldn’t stop the bleeding,” Amis said.

LaDonna had allegedly experienced an extreme version of what happens to millions of seniors in the U.S. every year. Financial exploitation is the most common form of abuse against elderly people.

But few have a backstory as bizarre — or as tragic — as LaDonna and St. James Davis.

They were crazy about cars.

In the 1970s, St. James was a professional boat racer-turned NASCAR driver. LaDonna was his crew chief, one of the first women on the circuit to hold the role.

But the real star of the Davis family was Moe the chimp.

St. James brought Moe home from Tanzania in 1967, and the Davises immediately treated him more like a son than a pet.

Moe would eat with them at the kitchen table and sleep in their bed. He was the best man at their wedding.

But in 1971, the city of West Covina sought to have Moe removed from the Davises’ home, setting up a courtroom showdown that ended with the judge showering the chimp with effusive praise.

“From what I’ve observed of Moe outside and in the courtroom, he doesn’t have the traits of a wild animal and is, in fact, somewhat better behaved than some people,” Judge Jack Alex said.

The Davises lived with Moe for nearly 30 years until he was forcibly removed from their home and placed in a wildlife sanctuary after he bit a house guest’s finger. On a trip to see him on his 39th birthday in 2005, the unthinkable happened.

Two other chimpanzees escaped from their enclosure just as St. James and LaDonna were preparing to eat birthday cake with Moe.

These chimps, Ollie and Buddy, charged the Davises. One bit off LaDonna’s left thumb, but it was St. James who bore the brunt of the attack.

The chimps gouged out his right eye and chewed off his nose, eight of his fingers, a chunk of his skull as well as parts of his lips, cheek, buttocks, genitals and feet.

The mauling went on for several minutes until a relative of the sanctuary’s owner ran out with a gun and shot the two chimps dead.

St. James spent five months in the hospital and underwent several surgeries. But he would never walk again, see out of his right eye or regain full use of his hands.

Moe, meanwhile, was transferred to a different facility in the San Bernardino mountains, and the Davises visited him often.

Then one day in 2008, a co-owner of the facility called with dreadful news.

Moe had disappeared.

He had apparently escaped from his enclosure after breaking off steel welds. The Davises’ launched a frantic search, but Moe was never seen again.

The chimp they had loved like a son for nearly 40 years was suddenly gone from their lives.

“I can talk for days about Moe,” St. James told me back then, choking back sobs as LaDonna, his 24-hour caretaker, consoled him. “I just miss him so much.”

I spent three days with the Davises for a story for Esquire magazine. In the many hours we spent together, they only talked at length about two subjects: cars and their missing chimp.

“I’m hoping that wherever Moe is,” LaDonna said, “he’s making good choices for himself.”

The Davises never had a lot of money, but they were awarded $4 million in a 2009 settlement related to the attack, according to the court docket.

Over the next several years, daily life got harder. St. James required constant attention, and LaDonna was in her early 70s and slowing down.

Longtime friends and neighbors fell out of touch and in some cases died, leaving the couple more isolated and vulnerable. Some men brought in to help out at their 1.5-acre Holt Avenue property would keep coming around, and the Davises’ possessions sometimes went missing.

“She just always wanted to help people,” said Michael McCasland, a longtime friend. “But everyone seemed to rip her off.”

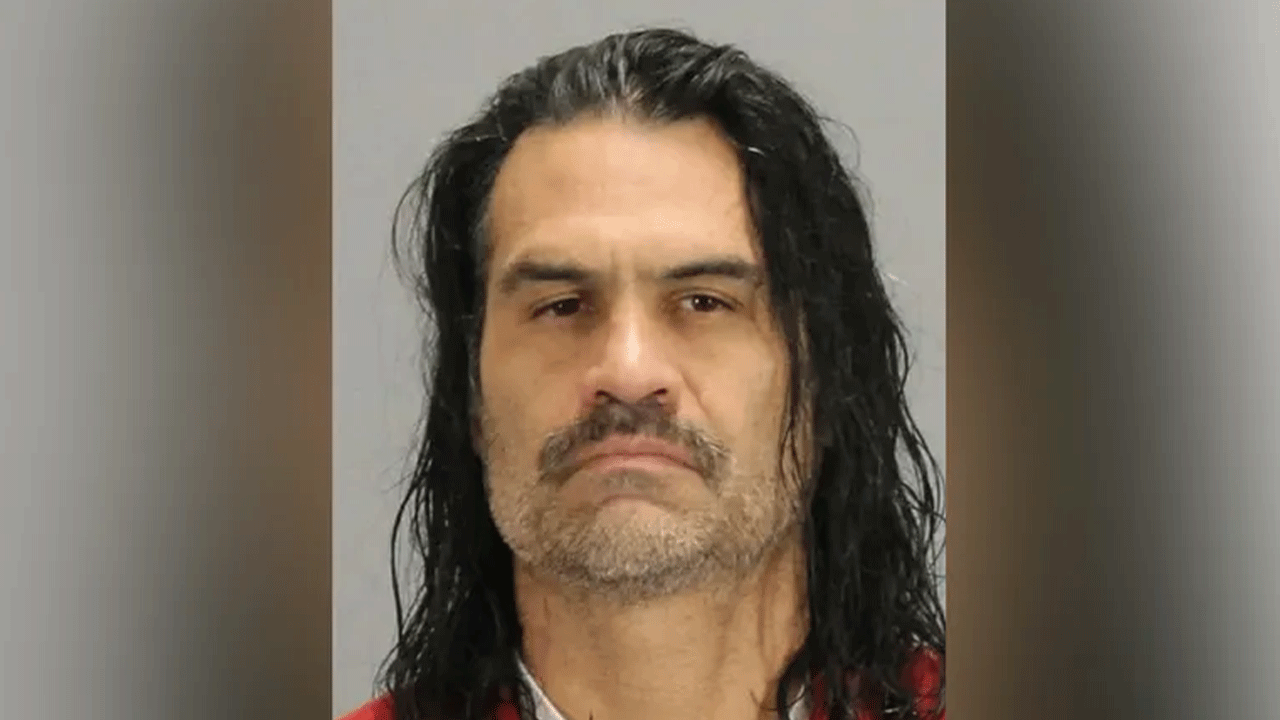

Then the Davises met a man who shared their love of cars, an immigrant from Myanmar named Min Zaw Maw.

Maw was introduced to the Davises in 2017. When he met St. James, the subject quickly turned to car engines.

Maw ran a company called Powertek Engineering Group that, according to its website, “designed the world’s best natural gas and propane engine combustion system.”

But he had apparently fallen on hard times.

He and his then-wife had been evicted from their apartment in nearby Arcadia after their landlord filed a lawsuit saying they had failed to pay the $2,250 monthly rent, according to a default judgment entered against them in July 2017.

Not long before he met the Davises, Maw pitched a local businessman on investing in his engine business.

“He had a good story,” said the businessman, Javier Puga, who was also a family friend of the Davises. “Then I found out he was full of it.”

Puga said he briefly allowed Maw to use a construction yard he owns.

“The guy was dead broke,” Puga said.

(Maw denies that he had money problems at the time, and he said that he was evicted for “working on an engine in the garage.”)

Maw moved his equipment to the Davises’ property on Holt Avenue and started spending more time there, he said in a deposition. In the Davises, he had met a couple who had sizable bank accounts and an impressive car collection. They were also in failing health and had no relatives.

Soon Maw was calling LaDonna “mommy,” and she was calling him “son,” a woman whom Maw installed to be LaDonna’s caretaker said in a deposition.

St. James was hospitalized in December 2017 after suffering a stroke.

That same month, a $50,000 check from one of the Davises’ accounts, made payable to Maw, was cashed, according to bank records cited by Ladonna’s court-appointed lawyer, Frank Piro, in court filings.

It was one of many questionable financial moves that would come under scrutiny.

In a three-month span, more than $260,000 was disbursed — either by withdrawal or check made payable to cash — from the couple’s accounts at Pacific Western Bank, according to a report Piro filed to the court. The report also noted that LaDonna prematurely withdrew nearly $250,000 from a CD account at a different financial institution, Citizens Business Bank, incurring a penalty of $2,500.

From August 2017 to December 2018, checks totaling at least $340,000 were signed by LaDonna and made out to Maw, his wife and a business entity he had created, according to a review of cleared checks that were obtained through a subpoena and provided to NBC News by McCasland, the longtime friend of the Davises.

(Maw said in court documents that he used the $50,000 check from LaDonna to cover labor costs on her properties and also to buy and sell hot rods on her behalf. But an email in response to questions from NBC News said he didn’t need money from LaDonna; it was LaDonna who needed financial assistance from Maw.)

During this period, the city of West Covina had been made aware of troubling activity at the Davises’ homes.

Friends had been calling police to report unfamiliar people at the house on Holt Avenue and a second one the couple owned on Vincent Street, according to a letter report by Amis, the code enforcement officer, that was based on contemporaneous notes chronicling his visits to LaDonna’s home from 2017 to 2019.

Officers visited the properties and spoke to the squatters, who claimed they had permission to live there and also to sell the vehicles that had accumulated in the backyards. When officers spoke to LaDonna, she seemed unaware of what was going on, Amis wrote.

But the police were in a bind. Since LaDonna told them the people on the property had permission to be there, there wasn’t much they could do.

In July 2018, St. James, 75, died of cardiopulmonary arrest.

He was once one of the most famous people in West Covina, yet there was no obituary, memorial service or news story about his death. Some of the Davises’ friends didn’t find out until several days later, which they now suspect was exactly how Maw wanted it.

One month before St. James died, McCasland went to check on LaDonna.

McCasland, a real estate agent, had been a family friend of the Davises since 2002. He acted as the couple’s spokesman after the chimp attack and Moe’s disappearance.

“They were like an older brother and sister to me,” he said.

McCasland showed up at LaDonna’s house after he tried to call her but got a message saying her phone was disconnected. When he arrived, a disheveled LaDonna told him she never wanted to see him again, McCasland said, leaving him stunned and confused.

“That’s when I knew there was a serious problem,” he said.

McCasland had previously been named the successor trustee of a Davis family trust that held their two properties.

But in the days after he went to check on LaDonna, a new living trust was created that named Maw as the successor trustee. The trust also named a beneficiary: Maw.

Maw was also given the authority to “conduct any business with any banking or financial institution with respect to any of” LaDonna’s accounts, according to a power of attorney document that she signed.

“Maw ingratiated himself with LaDonna and gained her trust,” McCasland said in a July 2018 court petition that sought to void any legal agreement between Maw and the Davises and to recover any money or property that was under his control.

McCasland’s filing accused Maw of exerting undue influence over LaDonna and also of selling off the couple’s valuables. It included a copy of an online ad for a $200 “vintage Nascar gas can” in which Maw’s first name and photo appeared in the section denoting the seller.

“I have hotrod parts, plowers, tools and of old things,” read the ad, which included a typo.

In court filings, Maw denied the allegations. He said that he had stepped in to help the couple with their basic needs after McCasland failed to do so.

Maw also accused McCasland of taking advantage of the Davises in a 2016 real estate deal, alleging among other things that he sold the property to a personal friend at a discounted price.

(McCasland denies the claim, and the buyer told NBC News he in fact had never met McCasland. The buyer also said he paid more for LaDonna’s property than for two larger buildings on the same street.)

As the legal case dragged on, the situation at the Davises’ homes turned more chaotic.

Fights broke out among the squatters. Calls to 911 multiplied. Code violations piled up.

Los Angeles County Adult Protective Services opened an investigation, which found that LaDonna was languishing in nightmarish conditions.

During a home visit in April 2019, workers found her in a room with spider wasps buzzing through the air and hundreds of rabbit feces covering the floor, according to a report by Diana Homeier, then-medical director of the Los Angeles County Elder Abuse Forensic Center, which includes representatives of Adult Protective Services and law enforcement agencies.

LaDonna was unable to state her age or the year, and many of her valuables were missing, the report said.

“She appears to be a victim of financial abuse,” Homeier wrote. “She clearly does not have the capacity to make decisions about her living situation, finances or personal care. Additionally, she is not able to see that she is being taken advantage of.”

At some point, the Holt Avenue property was taken over by members of the Mongols motorcycle gang who forced Maw out of the home, according to the report by Amis, the code enforcement officer.

A representative of the Office of the Public Guardian needed a police escort to visit the property because of the presence of the Mongols, LaDonna’s court-appointed lawyer later wrote in court papers.

“They have had, in the past, no problem going ‘head to head’ with the Hell’s Angels,” he wrote. “Needless to say, they are not paying any rent.”

Maw called 911 repeatedly to report that LaDonna was in danger. When officers responded, they found no evidence of such, but it was clear LaDonna was in a precarious position.

People in the house who described themselves as LaDonna’s caretakers told police they couldn’t administer her medication or bring her to doctor appointments because Maw “had all of the information and was keeping it to himself so he could ‘weasel’ his way back into LaDonna’s life,” according to the report by Amis.

In May 2019, a large contingent of police officers, Adult Protective Services workers and fire department personnel descended on the home. This time, LaDonna agreed to leave the premises in an ambulance and be taken to a hospital.

That LaDonna was finally in a safe place after a year of wellness checks came as a relief to Amis, but he was frustrated by how long it took.

“We have so many damn services, but we had this lady who was being taken advantage of right here, right now, and no one was coming to fix it,” Amis said in an interview.

With LaDonna now in the hospital, Maw opened a new legal front to maintain control of her money and properties.

He filed court papers in June 2019 seeking to become LaDonna’s conservator, a court-appointed guardian who would manage her finances and make health care decisions.

As is standard practice in conservatorship cases, the court appointed an attorney to advocate for LaDonna. The lawyer, Piro, visited her in the hospital and then filed a report to the court.

Asked if she “consented” to Maw becoming her conservator, LaDonna replied: “Definitely not,” according to Piro’s report.

But it was also clear that she wasn’t all there. LaDonna insisted that Maw was in jail and that the West Covina police chief had personally delivered the news to her, the report said.

A judge appointed Brett Hitchman, a professional fiduciary, to be the temporary conservator of LaDonna’s person and estate, but Maw kept up his quest to become her permanent conservator.

Piro filed additional reports to the court, raising concerns about the money withdrawn from her accounts and checks written out to Maw.

“I have advised her about the hundreds of thousands of dollars that supposedly she took out,” Piro told a judge at a hearing in October 2019. “And she’s adamant that, if that was done, it was done through forgery.”

LaDonna attended the hearing, as did Maw.

By then, two additional trusts had been created that named Maw trustee and beneficiary.

“Listen, Min used to work for me, and so did the gentleman behind him,” LaDonna told the judge, according to a court transcript, referring to another man in the courtroom.

“I don’t know how they think they can take things over from me. I never signed any paperwork over to them. If they have paperwork to that” effect, “it’s because they falsified my signature.”

“I don’t owe him anything,” LaDonna added, referring to Maw.

Moments later, Maw’s attorney, Juan Dotson, said his client would end his bid to be LaDonna’s conservator.

Dotson noted that he had filed a document that showed Maw had spent $275,000 of his own money to maintain LaDonna’s properties. (Four months earlier, Maw had said in court papers that he spent $70,000.)

The attorney for McCasland, the Davis friend who initially accused Maw of taking advantage of LaDonna, told the judge that Maw’s accounting document raised more questions than answers.

Of the $275,000, less than $2,000 was used for her care, said the attorney, Michael Ebiner.

“The rest of the $275,000 is for, apparently, repairs, maintenance, cars,” Ebiner said. “There’s a $13,000 item that says ‘ask my accountant.’”

The judge, Gus May, appointed Hitchman as conservator of LaDonna’s estate, ruling that there was “clear and convincing evidence” that LaDonna “is unable to care for her personal or financial affairs and is subject to undue influence.”

LaDonna was still in the hospital, but her insurance was running out and there was no money available to her in any of her accounts, according to court filings by her lawyer.

But Hitchman ultimately discovered that she still had $440,000. The cash had been held in a Bank of America trust account that Maw had been administering and that the bank closed after it was flagged as “suspicious or subject to fraud,” Hitchman said in court filings.

Hitchman also sold the Davises’ homes for roughly $2 million, providing her a sizable nest egg.

LaDonna, now 80, was moved from a hospital to a facility that specializes in caring for people with cognitive issues. The legal battle over whether to void the new trusts carried into late 2022.

Maw maintained that he had spent hundreds of thousands of dollars of his own money on LaDonna’s properties and for the storage of cars that he moved off of them.

(Maw was previously sanctioned by the court in the amount of $1,225 for failing to produce receipts or any other documents to support his contention that he had spent $275,000 of his own money. Maw said in court filings that the documents were stolen from LaDonna’s house.)

A settlement was reached in November 2022. It granted Maw $175,000 in cash and all of the vehicles purchased by LaDonna “and/or funds belonging to LaDonna that are currently in his possession.”

The settlement avoids the “significant expense of further litigation” and secures LaDonna’s assets, Hitchman wrote in court papers.

Hitchman declined to comment.

Ebiner, the lawyer who represented McCasland, said Maw had leverage in the mediation talks because it would be difficult to prove both that LaDonna didn’t understand she was giving him control of her finances and that he had exerted undue influence over her.

Amis, the code enforcement officer, was shocked when I told him about Maw’s payout.

“Are you serious?” he said breathlessly.

Elder abuse experts say it’s not uncommon for cases to end in settlements because of the high costs of ongoing litigation. And prosecutors are reluctant to bring charges because cases involving a mentally compromised victim tend to be difficult to win.

“It’s really frustrating,” said Dr. Stacey Wood, a clinician with Adult Protective Services in Los Angeles and a professor of psychology at Scripps College. “If somebody kicked in a door, took a bunch of stuff and left, the police would have no trouble charging him.”

Not prosecuting the fraudsters has serious consequences, Wood added.

“It leaves the criminals free to look for new victims.”

I reached out to Maw on a Thursday afternoon. He called me back the next day, and we spoke for over an hour.

It was a bewildering conversation.

Maw described himself as someone who came to the rescue of two elderly people and got caught up in a system he didn’t understand.

“I saw that they needed help, and I tried to help,” Maw, 64, said. “That’s all.”

He said it was the Davises who pushed the idea of him taking over their trusts even though they had known each other for less than a year. “I don’t know about trusts,” Maw said. “I’m an Asian guy. We don’t have that.”

He said he didn’t want to sign the documents, but LaDonna insisted. Then he tried his best to take care of the couple and help to clean up and secure their property, only to get drawn into an extended legal battle that hurt his finances and damaged his marriage.

But when I asked pointed questions, Maw’s answers were convoluted.

Why was there a $9,500 check written out to your wife?

“It was a motor T, a motor T or something,” he said. “I explained everything. Here this is right here and this is what she paid.”

When I noted that he was evicted from his home around the same time he met the Davises — he hadn’t paid his rent — Maw at first blamed it on an unkempt garage.

“I was doing the garage over there and it was dirty,” he said. “That was the issue. They already know.”

He kept talking, veering from his daughter getting into medical school to his time working overseas for a German company — “I lived hotel to hotel. I’ve been jumping around everywhere in the world” — and ending with him saying he could give me a list of all his landlords over the years.

“You can call,” he said. “How many times I’m late and how many years I lived there? You can find out.”

Maw also promised to send me all the receipts documenting how LaDonna’s money was spent, paperwork showing all the jobs he missed out on during this period and his correspondence with banks and various people involved in the case.

But I never received any of these things.

After I followed up with him, the situation only got stranger.

I received a text message from his lawyer, Harold W. Dickens, saying he heard I was planning to publish a story about Maw that “contains falsehoods” and that if I did so they would file a lawsuit seeking “maximum damages as well as punitive damages for your bad faith.”

“Govern yourself accordingly,” read the final line of the text message.

I sent a list of questions to Dickens via email. A week later, an unsigned email landed in my inbox from justice4Ladonna@gmail.com.

There were brief answers to my questions and a link to a Google Drive folder that included selected court filings, a letter from a LaDonna “caretaker” praising Maw’s treatment of her and two cellphone videos of LaDonna criticizing McCasland.

The videos were taken while she was at home and Maw was still overseeing her finances.

In one of the clips, LaDonna denounces McCasland for doing unspecified “bad things.”

“Is anybody forcing you to do this? To say this?” an unseen man asks her.

“No, I’m doing this of my own free will,” she replies.

Then the video cuts off.

Whoever sent the email didn’t include any evidence, like receipts or bank statements, that showed Maw spent his own money on LaDonna or that explained why he had received hundreds of thousands of dollars from her.

The name of the email account — justice4Ladonna — jibed with how Maw had portrayed himself and LaDonna as victims in our conversation.

He lamented that he had been cut off from communicating with her and that she had been taken to a facility and had her homes sold without her consent.

“It’s all about money,” Maw said. “That’s what this case is.”