Americans have benefited from huge leaps in breast cancer treatment over the last two decades, but diagnoses are becoming more common, especially among younger women, according to a report published Tuesday by the American Cancer Society.

The new report shows that breast cancer mortality has decreased by 44% since the late 1980s. Rates of breast cancer, however, have increased by 1% every year since 2012. In younger women, rates have increased at a faster clip — by about 1.4% every year since 2021.

“That is very alarming because we know that screening only starts at age 40,” said Dr. Sonya Reid, a breast medical oncologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, who was not involved with the report. “It’s not just one racial or ethnic group affected, we are seeing it across the board, so it’s hard to link it to ancestral or genetic factors alone.”

Still, the report showed differences among groups. Among Asian American and Pacific Islander women under 50, breast cancer diagnoses have increased by 50% since 2000. Breast cancer rates in AAPI women younger than 50 are now higher than those in Black, Hispanic and American Indian and Alaska Native women of the same age group. In 2000, AAPI women under 50 had the second-lowest rates of breast cancer.

The reason why more women younger than 50 are getting breast cancer is not clear, but Reid said it’s likely due to modifiable risk factors such as environmental exposures in food, air or water, rising rates of obesity and sedentary lifestyles — the same risk factors thought to be causing higher rates of colorectal cancer in younger people.

Dr. Wendy Wilcox, chief women’s health officer at New York City Health + Hospitals, said that it’s likely not just one factor alone is driving the increase in younger breast cancer diagnoses.

“There are all sorts of ideas we can throw out as to the reasons why, but until it’s studied we won’t know for sure,” Wilcox said.

The report also highlighted a stark racial disparity that has persisted for decades — Black women are still more likely to die of any type of breast cancer than white women.

“To see a 44% decrease in mortality is incredibly gratifying, but these gains have not been seen equally in all populations,” Dr. William Dahut, chief scientific officer for the American Cancer Society, said during a media briefing on Monday.

This was not always the case, he said: In 1970, Black and white women had the same mortality rates for breast cancer. Today, Black women are 5% less likely to get breast cancer than white women, but are nearly 40% more likely to die from the disease. The American Cancer Society researchers noted that this disparity is seen in even the most treatable types of breast cancer.

“For a long time, the community had thought the disparity is largely due to the higher rates of triple-negative breast cancer, but this shows Black women are more likely to die from all subtypes of breast cancer,” Reid said. “These advances that we have seen are really due to improvements in therapeutic advances and early detection, and we know if there are inequities in access to these improvements, we will see a widening in these disparities.”

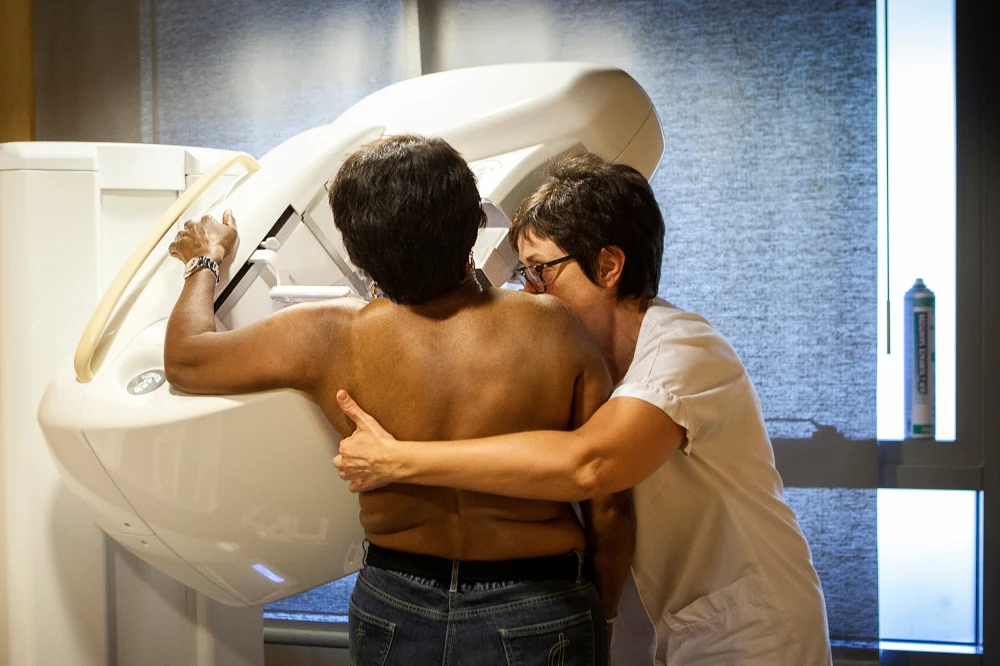

American Indian and Alaska Native women have a 10% lower chance of getting breast cancer than white women, but are 6% more likely to die from it, the report found. Just over 50% of these women over 40 had gotten a mammogram in the past two years, compared to nearly 70% of white women. The report also found that Hispanic women are also less likely to be screened than white women.

Compared to white women, Asian American and Pacific Islanders, American Indian and Alaska Natives, Black and Hispanic women are all more likely to develop breast cancer at a younger age, the report found. However, AAPI and Hispanic women have similar mortality rates to white women.

To close disparities, the nation will have to expand access to early screening and the best cancer treatments, Wilcox said.

“Health care dollars are not allocated equitably across everyone in our country,” she said.

Even for those with insurance, coverage varies greatly, and a person’s ability to take off work for a mammogram or care and whether they live near a cancer center also play key roles in access, Wilcox said. Each person’s family and personal history and genetics will also determine when they should start screening for breast cancer.

“Moving forward, we really need to make sure we have wide access to effective treatments for all of our patients,” Reid said. “We have seen that despite more effective drugs, the racial disparity gap has not budged. Another drug is not going to do it.”