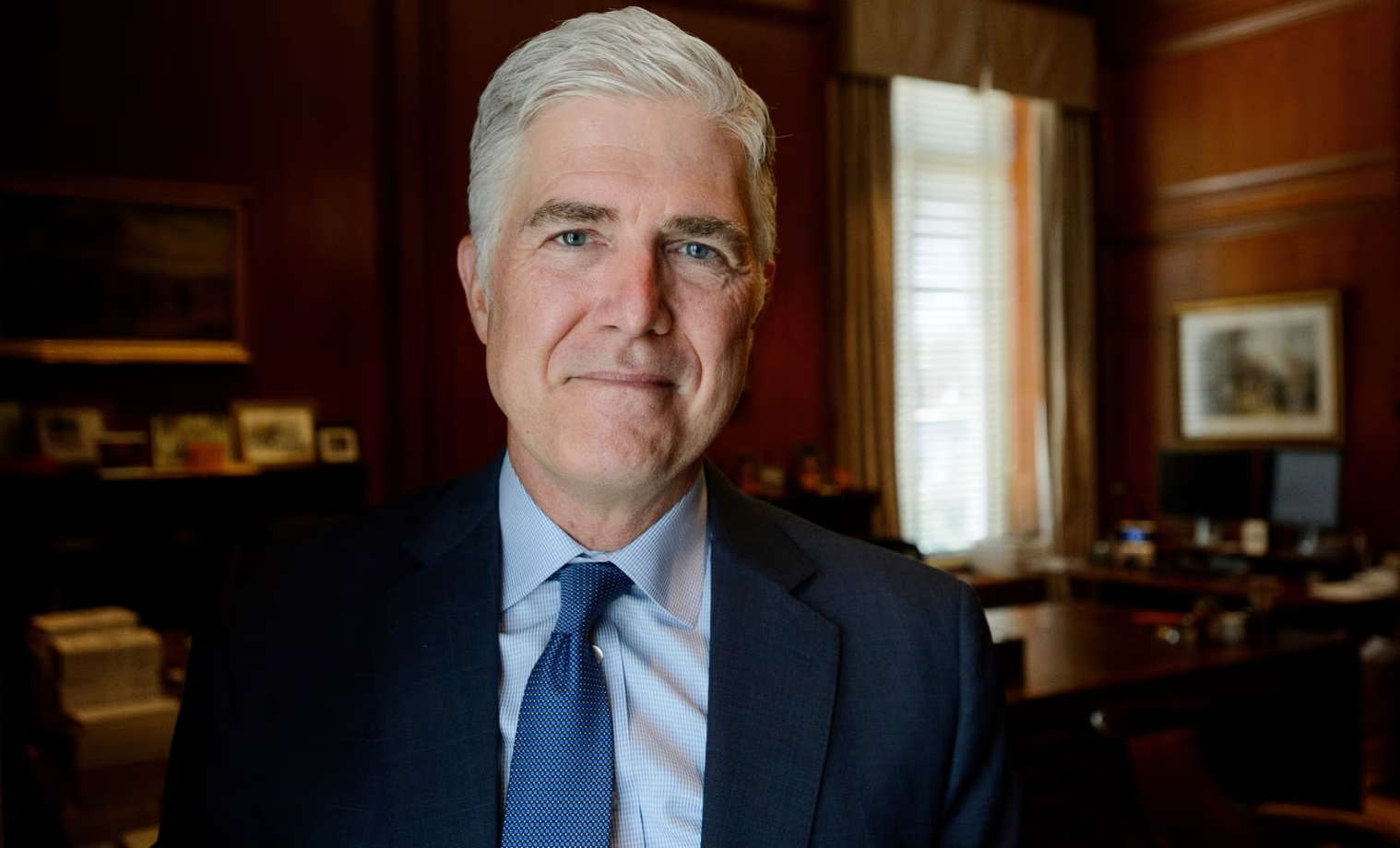

Supreme court justice says ‘too much law’ impairs liberties and talks about importance of an independent judiciary

US supreme court justice Neil Gorsuch has said ordinary Americans are “getting whacked” by too many laws and regulations in a new book that underscores his skepticism of federal agencies and the power they wield.

“Too little law and we’re not safe, and our liberties aren’t protected,” Gorsuch told the Associated Press in an interview in his supreme court office. “But too much law and you actually impair those same things.”

Over Ruled: The Human Toll of Too Much Law is being published Tuesday by Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Gorsuch has received a $500,000 advance for the book, according to his annual financial disclosure reports.

In the interview, Gorsuch refused to be drawn into discussions about term limits or an enforceable code of ethics for the justices, both recently proposed by Joe Biden at a time of diminished public trust in the court.

Supreme court justice Elena Kagan, speaking a couple of days before the president’s proposal, separately said the court’s ethics code, adopted by the justices last November, should have a means of enforcement.

But Gorsuch did talk about the importance of judicial independence. “I’m not saying that there aren’t ways to improve what we have. I’m simply saying that we’ve been given something very special. It’s the envy of the world, the United States judiciary,” he said.

Gorsuch echoed that stance in an interview Sunday on Fox News, remarking: “I just say: Be careful.

“The independent judiciary … What does it mean to you as an American? It means that when you’re unpopular, you can get a fair hearing.”

The 56-year-old justice was the first of three supreme court nominees confirmed during Donald Trump’s presidency. Trump’s appointees have combined to entrench a conservative majority that has overturned the federal abortion rights once granted by Roe v Wade, ended affirmative action in college admissions, expanded gun rights and clipped environmental regulations aimed at climate change, as well as air and water pollution more generally.

In July, the supreme court completed a term in which Gorsuch and the court’s five other conservative justices delivered sharp rebukes to the administrative state in three major cases, including the decision that overturned the 40-year-old Chevron decision that had made it more likely that courts would sustain regulations. The court’s three liberal justices dissented each time.

Gorsuch also was in the majority in ruling that former presidents have broad immunity from criminal prosecution in a decision that indefinitely delayed the election interference case against Trump. What’s more, the justices made it harder to use a federal obstruction charge against people who were part of the mob that violently attacked the US Capitol on January 6 2021 in an effort to overturn Trump’s defeat by Biden in the 2020 election.

Gorsuch defended the immunity ruling as necessary to prevent presidents from being hampered while in office by threats of prosecution once they leave.

The court had to wrestle with an unprecedented situation, he said. “Here we have, for the first time in our history, one presidential administration bringing criminal charges against a prior president. It’s a grave question, right? Grave implications,” Gorsuch said.

But in the book, co-authored by a former law clerk, Janie Nitze, Gorusch largely sets those big issues aside and turns his focus to a fisherman, a magician, Amish farmers, immigrants, a hair braider and others who risked jail time, large fines, deportation and other hardships over unyielding rules.

In 18 years as a judge, including the past seven on the supreme court, Gorsuch said, “There were just so many cases that came to me in which I saw ordinary Americans, just everyday, regular people trying to go about their lives, not trying to hurt anybody or do anything wrong and just getting whacked, unexpectedly, by some legal rule they didn’t know about.”

The problem, he said, is that there has been an explosion of laws and regulations, at both the federal and state levels. The sheer volume of Congress’s output for the past decade is overwhelming, he said, averaging 344 pieces of legislation totaling 2m to 3m words a year.

One vignette involves John Yates, a Florida fisherman who was convicted of getting rid of some undersized grouper under a federal law originally aimed at the accounting industry and the destruction of evidence in the Enron scandal. Yates’s case went all the way to the supreme court, where he won by a single vote.

“I wanted to tell the story of people whose lives were affected,” Gorsuch said.