Powerful weight loss medications aren’t reaching the people who need them most, according to researchers from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

The barriers to the drugs are many: Getting a prescription; finding a pharmacy with the drug in stock and being able to pay for it.

“Obesity has been a long-standing clinical and public health change and it’s growing in scope,” said Dr. Chiadi Ndumele, director of obesity and cardiometabolic research in the division of cardiology at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, who presented the findings Tuesday at an American Heart Association meeting in Chicago. The findings have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

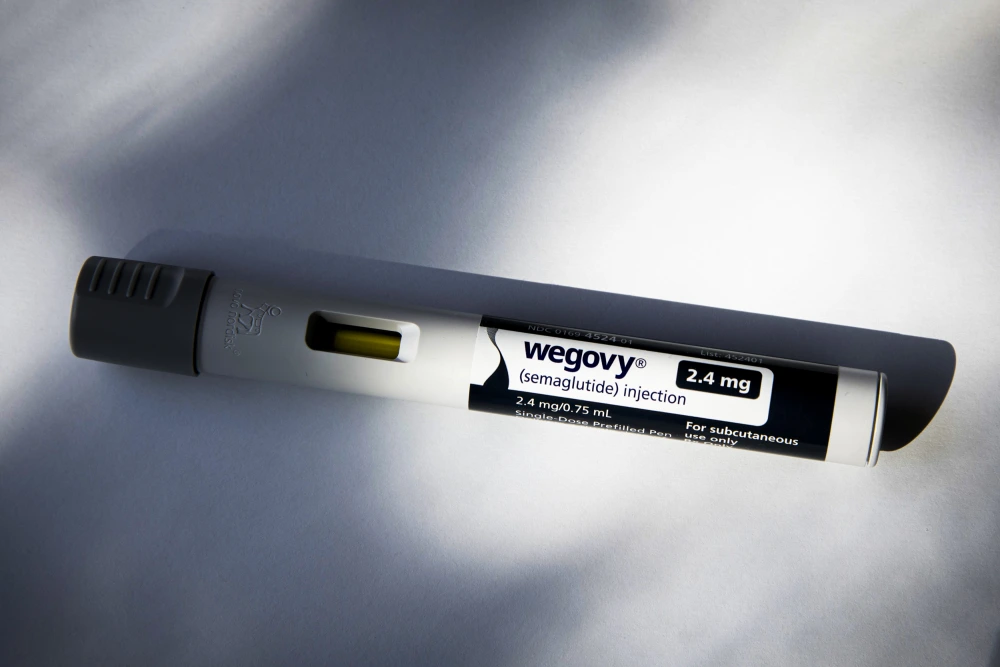

“In recent years, we’ve developed increasingly powerful pharmacotherapies, particularly these GLP-1 receptor agonists, that have a fairly profound impact on obesity,” he said, referring to the class of drugs that includes Ozempic, Wegovy and Zepbound.

“That being said,” Ndumele said, “we still recognize that the uptake of these agents is still fairly limited.”

The new findings come shortly after NBC News reported on the deep racial and geographical disparities seen in the United States among those who are prescribed a weight loss drug.

Insurance, in particular, can be a major obstacle, given the drugs’ expensive list price, averaging around $1,000 a month. But the Hopkins researchers found that even among patients whose insurance did cover the drugs, getting a doctor to write a prescription was still unlikely — even rare.

“Coverage is very important, but coverage is only part of the story,” Ndumele said.

The study looked at health records from 18,000 patients who had gone to a Johns Hopkins outpatient clinic from January to September 2023.

All had obesity, meaning a body mass index of at least 30, and all had insurance coverage for the medications.

Only 2.3%, however, the researchers found, were prescribed a weight loss drug.

That figure did not come as a surprise to Ndumele, who said that factors such as the cost of copays and the hassle of obtaining prior authorization may be among the reasons that people didn’t get prescriptions.

There is also “an additional question of how comfortable we currently are in engaging in the obesity conversation with patients,” Ndumele said. “I’m a physician who focuses a lot on obesity and I can tell you, in terms of research and clinically, I can tell you that there’s often some who are not always the most adept at raising the conversation of obesity. As a result, it often goes underaddressed in clinical environments.”

That, coupled with weight bias and weight stigma, he said, can impact how the topic of weight loss drugs may come up.

Among the small sliver of patients who did get a prescription for a weight loss drug, disparities were apparent: Over all, white adults were more likely to get a prescription than Asian or Black adults.

Adults with a BMI of 35 or more, hypertension, or Type 2 diabetes also had a higher likelihood of getting a prescription. However, the discrepancy between white and Black adults still held, with white adults more likely to get a prescription, despite higher rates of severe obesity and hypertension among Black adults.

Adults in their 40s were more likely to get a prescription compared to other age groups, the researchers found. Women were more likely to get a prescription than men.

Ndumele noted that the 18,000 study participants visited a wide range of outpatient clinics at Johns Hopkins and were not limited to primary care or weight-related care. Some may have gone to a dermatologist or a gynecologist, for example. A patient’s weight and weight loss medications may not have been the subject of the visit.

Dr. Christopher Chapman, a gastroenterologist who is certified in obesity medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said that additional factors such as in-office conversations and medication shortages may also play a role in the limited number of prescriptions written.

“If you fix the insurance issue, you’re getting a head start but not necessarily solving all the barriers that are going to prevent you from getting these medications,” Chapman said.

“Overall, this is a bigger and more complex problem and it is unlikely that providing universal insurance coverage in isolation will lead to future equitable access,” he said.

Dr. Sahar Takkouche, chief medical officer for Vanderbilt Wilson County Hospital and an obesity medicine specialist, said that more physicians need to be trained in obesity medicine so that they’ll feel comfortable discussing these drugs with their patients.

“There’s a ton of misinformation out there and there’s a limited amount of people who have knowledge to be able to prescribe” weight loss drugs, she said.