Haley’s rhetoric on gender reflects the tension of appealing to voters who want to be part of making history and those who don’t think that’s a good reason to pick her.

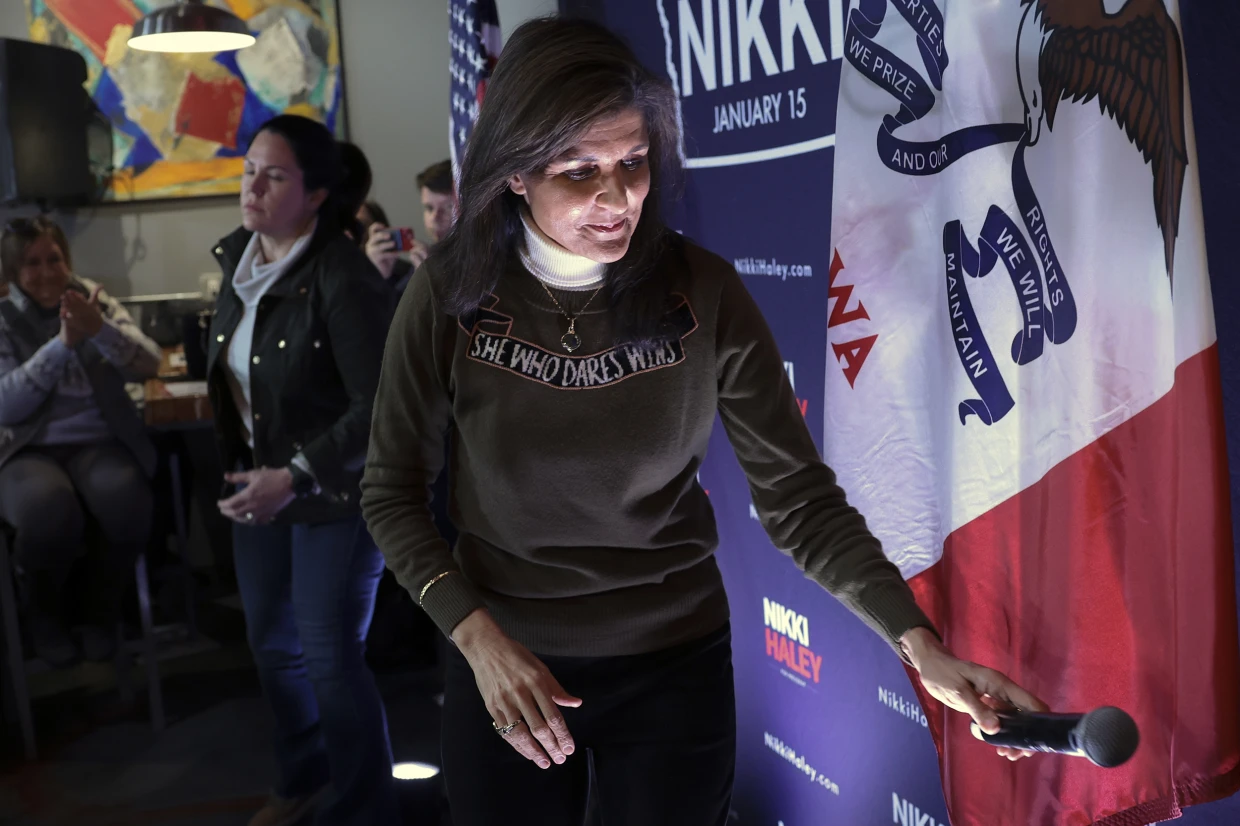

IOWA CITY, Iowa — She campaigns in sweaters that declare, “She who dares wins.” She brushes off attacks from her opponents as pettiness from “the fellas.” Her heels, she says, were made for kicking.

But when Nikki Haley asks voters to help her make history, she says it’s not that history.

“Think of the fact that you might be making history in this moment,” the former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations told Iowa voters in a weekend swing through Cedar Falls ahead of Monday’s first-in-the-nation GOP caucuses. “And I’m not talking about history of a female president. I’m talking about history saying we are going to finally right the ship in America. We’re finally going to get it right.”

It’s a tricky balancing act that may best be understood through the lens of a candidate who has built a cross-party coalition with a range of views on how, if at all, to prioritize her gender.

“I honestly had a conversation with a few of my players,” said Polk County resident Paul Samson, 48, who coaches a youth women’s volleyball team and switched from supporting Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis to backing Haley. “I have a chance on my side of the aisle to elect a woman for president.”

Both candidate and campaign are aware that her status as the lone woman in a field of male candidates is an asset with some voters — 43% of her supporters in Iowa say they would vote for President Joe Biden over Republican front-runner Donald Trump — and a liability with others. She is, after all, campaigning for the nomination of a Republican Party in which many voters abhor “identity politics” and reject the concept that they would pick a candidate based on her gender.

“I vote on issues,” Forrest Levielle, an Iowa caucusgoer who is likely to back Haley, told NBC News. “I’m a registered Republican. … You vote on issues, on what we feel is the best candidate for us.”

He added that he’d thought about the potential for Haley to shatter the last glass ceiling in politics, but “it doesn’t really matter to me.”

The NBC News/Des Moines Register/Mediacom poll released Sunday showed Haley in second place in Iowa with 20%, 4 points ahead of DeSantis but 28 points behind Trump. In New Hampshire, where independent voters are expected to give her a boost again, she is running a closer second to Trump in recent surveys.

Even as Haley courts independents and Democrats, who can choose to caucus with Republicans on Monday, DeSantis’ allies are comparing her to 2016 Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton — a longtime GOP foil — in ads here.

“Next thing you know, they’ll call her Nancy Pelosi, the South Carolina Nancy Pelosi,” said former Polk County Republican Party Chair Will Rogers, who plans to caucus for Haley, adding that the Clinton line of attack “is gender-specific.”

Clinton famously leaned away from her gender in her failed 2008 effort to win the Democratic nomination against Barack Obama, who often spoke of history without making his race an explicit part of his appeal. In 2016, Clinton won her party’s nod while embracing feminism but lost to Trump in the general election.

The history she made as the first woman nominated by either major party for president — and the narrowness of her loss — helped convince a bumper crop of Democratic women to run for the presidency in 2020. Ultimately, Democrats picked a man, Biden, to match up against Trump that year.

Rogers thinks Haley’s gender is more of plus than a minus with Iowa voters, who have elected women — Kim Reynolds and Joni Ernst — to the governorship and one of the state’s two Senate seats.

“Have we moved into a post-gender political world? I’m not suggesting that in its entirety,” he said. “I think we’ve moved into where women can be expected to be strong leaders with an important voice in politics.”

As for how it affects Haley’s campaign, Rogers said gender is one of the ways she has been able to distinguish herself from the pack with certain sets of voters.

“That’s giving her some advantage with undecided voters,” he said. “And maybe it’s also attracting — I would call it nontraditional Republican voters.”

Former California Rep. Mary Bono, R-Calif., says she would like to see a woman win the presidency, but not because of her gender.

“I don’t believe people should vote for that reason,” Bono said. “I believe a leader will rise to that occasion and then that will happen.”

That’s why she plans to endorse Haley after watching the Republican primary unfold over the past year or so.

“Nikki has risen through this scrum,” Bono said in a telephone interview. “She’s duking it out, and that in and of itself is going to prove to people that she’s a strong leader.”

Haley’s campaign is freighted with the tension of communicating to voters who want to be part of making history and those who don’t want to be told that’s why they should pick her. That can make for some unexpected rhetorical turns on the campaign trail. In one now-familiar refrain, she focuses voters intently on empowering women — to make a social policy point about protecting girls.

“We need to raise strong girls, because strong girls become strong women, and strong women become strong leaders,” she said in Ankeny earlier this week. “And none of that happens if you have biological boys playing in girls sports.”