The Food and Drug Administration did not approve an epinephrine nasal spray that would have been the first needle-free alternative to epinephrine autoinjectors, including EpiPens.

The agency told drugmaker ARS Pharmaceuticals that it needed to conduct another study on the drug, called Neffy, to support approval, the company said in a statement late Tuesday night.

The rejection came despite the agency’s advisory committee in May voting to recommend approval of the drug in children and adults. It’s rare that the FDA does not approve drugs recommended by its committees.

“We are very surprised by this action,” Richard Lowenthal, the CEO of ARS Pharmaceuticals said in the statement.

The company said it is going to appeal the FDA’s request for additional data.

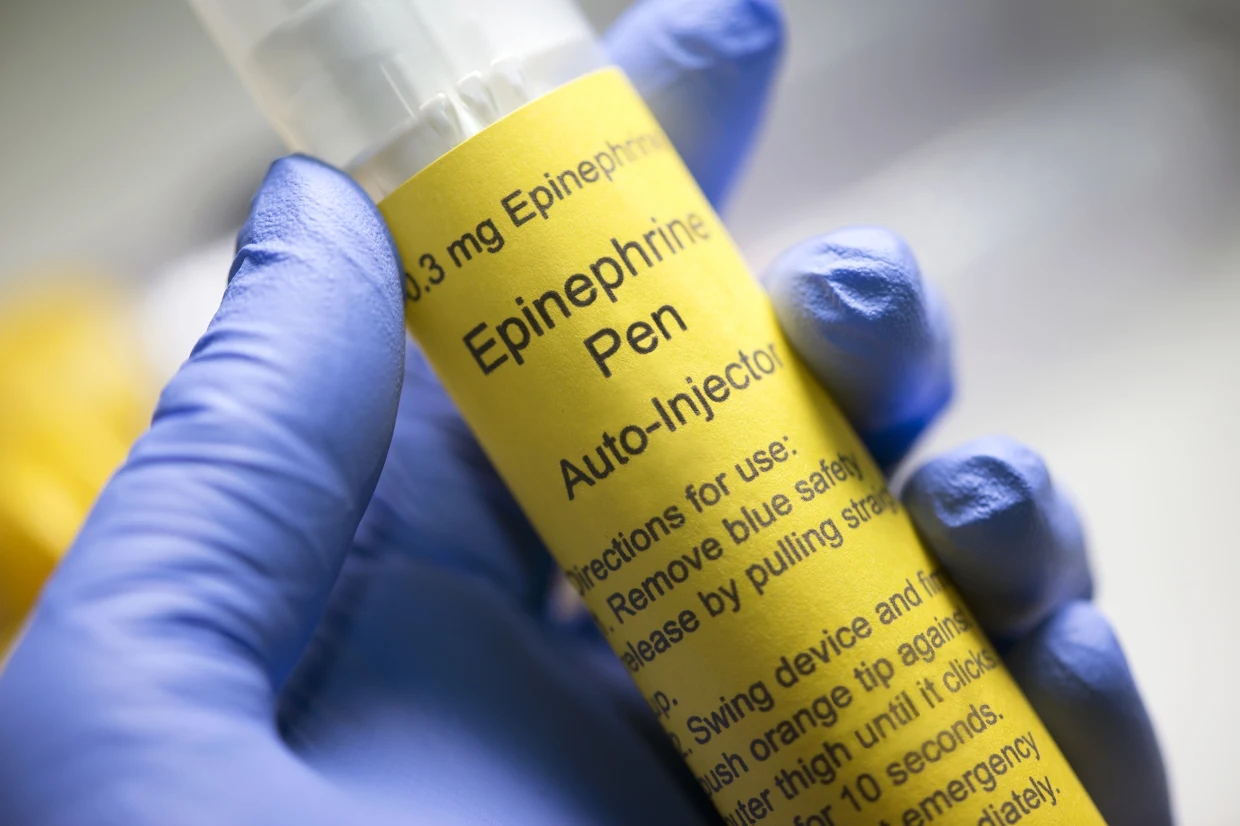

Epinephrine has been used in the U.S. since 1901 and is highly effective in reversing anaphylaxis, the most severe type of allergic reaction. Anaphylaxis can happen within minutes of being exposed to an allergen, such as a peanut or cat dander. Without treatment, it can be deadly.

All currently available epinephrine treatment options, however, must be injected, which can be a problem for people who are afraid of needles.

“I’m shocked,” Dr. Zachary Rubin, an allergist at Oak Brook Allergists in Illinois, said of the FDA’s decision.

“There are no alternatives right now,” said Rubin, who is not a member of the FDA’s advisory committee. “You basically have epinephrine autoinjector devices, needle options, and people have been clamoring for years to get a needle-free option.”

A major point of concern during the May advisory committee meeting was a lack of clinical data, particularly the fact that the drug was not studied in people experiencing anaphylaxis.

ARS Pharmaceuticals said that the nasal spray was “comparable” to an EpiPen, based on studies conducted in animals as well as in people without anaphylaxis.

Despite its concerns, the panel ultimately voted 16-6 in favor of the drug for use adults, and 17-5 in favor of the drug use in children.

For Dr. Maryann Amirshahi, a professor of emergency medicine at Georgetown University School of Medicine and a member of the advisory committee, the lack of data in patients with anaphylaxis was a sticking point. She voted against the drug both times.

“I listened to the parents in the hearing and I heard them talk about how traumatic it was to give their children a shot,” Amirshahi said in an email to NBC News on Tuesday. “But to me, as a parent, panel member, pharmacologist, and ER doc who has seen her fair share of anaphylaxis, the scary thing was not the shot, but a drug failing in treating a life-threatening condition.”

Studying a drug meant to be an emergency treatment for life-threatening allergic reactions raises thorny ethical questions.

In order to do a randomized controlled trial, adults and children suffering from a severe allergic reaction would either receive the treatment or a placebo, a scenario that would be unethical, Rubin said.

Amirshahi said that it is possible drug could be studied in people experiencing anaphylaxis in an allergist’s office or an emergency room where there would be a fail-safe treatment on hand.

She said that she’s hopeful that the FDA’s rejection will allow for time to study the drug properly and make sure it is effective.

“While I think the drug has merit, it doesn’t have adequate efficacy data at this point,” she said.

The FDA has requested an additional study comparing Neffy to an epinephrine autoinjector in people with allergen-induced nasal symptoms including sneezing, itching and congestion.

The drugmaker said it plans to resubmit its application to the FDA in the first half of 2024.