When Claire Shubik-Richards heard a convicted murderer had escaped from a county-run prison in Pennsylvania, she said one of the first things to cross her mind was whether it had to do with an ongoing staffing crisis at the facility where the inmate absconded.

Shubik-Richards, executive director of the Pennsylvania Prison Society, the de facto independent monitor of prison and jail conditions in Pennsylvania, told ABC News that an annual survey her organization does of lockups in the Keystone State showed the Chester County Prison, the facility where inmate Danelo Cavalcante escaped from, is severely understaffed.

The 2022 survey also found the prison had funding for 243 full-time prison staffers, but only 178 of those positions were filled.

On Aug. 30, a day before Cavalcante’s escape, Chester County Prison officials said at a prison board meeting that the facility had funding for 301 full-time positions and that 34 remained unfilled. As of July, 720 inmates were incarcerated at the Chester County Prison, an increase of 96 from a year earlier.

She said the understaffing at Chester County Prison is indicative of what’s going on at county jails and prisons throughout the state and nation.

She said the Philadelphia Industrial Correctional Center, a city-run jail, is 30% understaffed for the more than 900 inmates it normally has in custody.

On May 7, two inmates at the Philadelphia Industrial Correction Center escaped. One of the escapees, 18-year-old Ameen Hurst, had been charged with four counts of murder. He and inmate Nasir Grant, 24, escaped from the jail through a hole in the recreation yard’s fence, officials said. Both men were captured days later without incident, officials said.

“For the last five years, the maximum number of escapes reported annually [in Pennsylvania] has been three. This year alone, we know that there are six escapes,” Shubik-Richards said. “And it’s not a coincidence. We don’t have the number of staff needed for the number of people we have in custody.”

Two of the escapes this year occurred at the Chester County Prison, including Cavalcante’s breakout.

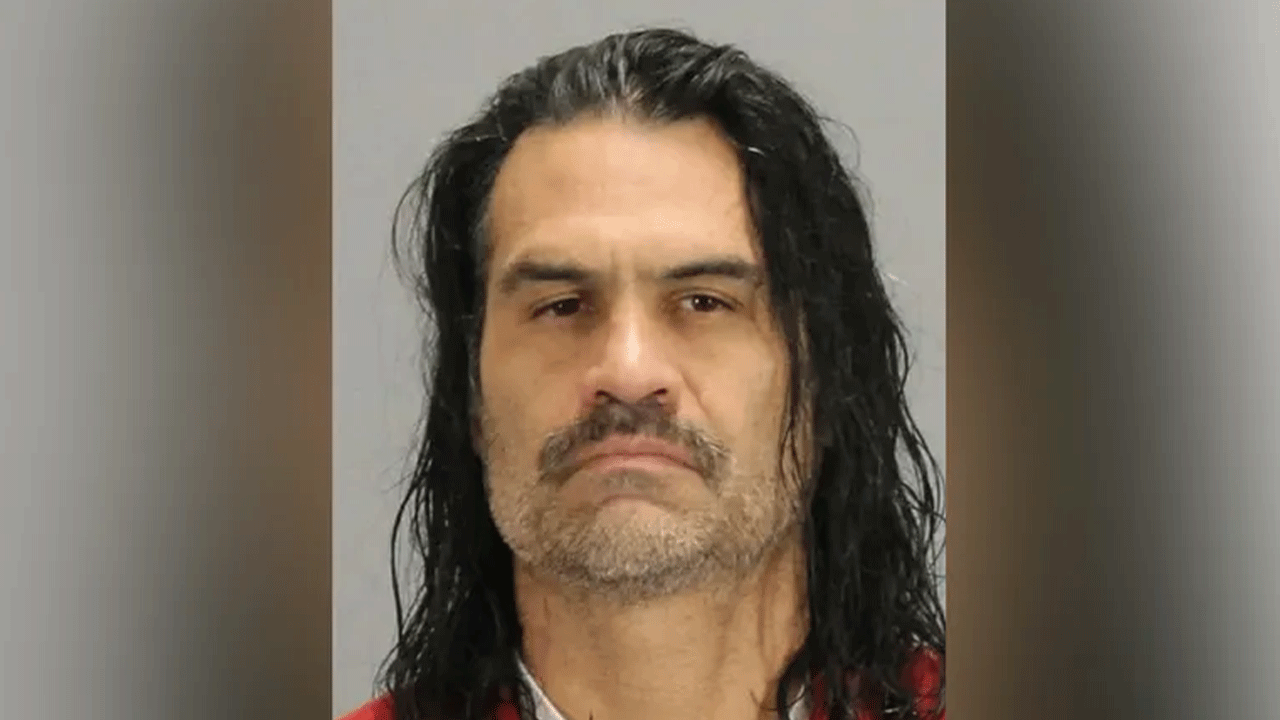

Cavalcante was captured alive on Wednesday following a 14-day manhunt that left residents of Chester County, one of the wealthiest counties in Pennsylvania, afraid for their safety after authorities described the fugitive as “dangerous” and advised them to keep their doors and windows locked and be vigil.

Cavalcante, who officials said is also wanted in his native Brazil on homicide charges, escaped from the Chester County Prison in Pocopson Township on Aug. 31. He was noticed missing that morning about an hour after his escape when inmates returned from the exercise yard at the prison, where he was being held pending transfer to a state correctional institution.

The former fugitive followed the same method of escape and route used by an inmate at the Chester County Prison, Howard Holland, acting warden of the prison, told reporters. Inmate Igor Vidra Bolte broke out of the prison in Pocopson Township on May 19 by scaling a wall in an exercise yard to gain access to the roof, according to a criminal complaint obtained by ABC News.

Cavalcante escaped from the prison by “crab walking” up a wall, pushing his way through razor wire installed after Bolte’s escape, running across the prison roof and scaling more razor wire, before jumping down to a less secure area to make his getaway, Holland said.

Holland noted that “one key difference” between the two escapes was the actions of a tower guard whose primary responsibility was to monitor inmates in the exercise yard.

“In Bolte’s escape, the tower officer observed the subject leaving the yard area and contacted control immediately. That is why Bolte was apprehended within 5 minutes,” Holland said. “In the escape of Cavalcante, the tower officer did not observe nor report the escape. The escape was discovered as part of the count that occurs when the inmates come in from the exercise yard.”

Shubik-Richards said she could not evaluate the performance of the tower guard in the Cavalcante’s case. But “this is not an issue of one guard in one tower,” she added.

“Poor staffing ratios are a vicious cycle,” Shubik-Richards said. “Because when you don’t have enough staff, the staff you do have are forced to work extraordinary hours of overtime. And when you have tired, disgruntled staff, often operating on fumes, that’s not safe for the staff themselves. That’s not safe for the people in their custody. And, as we’ve seen, it can be not safe for the community.”

Jeff Mellow, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Manhattan, told ABC News that escapes as a whole are extremely rare, but that research indicates that county jails and prisons experience more breakouts than larger long-term lockups like state and federal prisons.

“Oftentimes they have fewer resources than state and federal facilities,” Mellow said. “So many of our jails and prisons across the country are understaffed and they are just not being resourced properly.”

He noted that there is only so much that can be done to prevent escapes.

Pennsylvania requires state inspections of county prisons like the one in Chester County, but those inspections are not required to include checking facilities for escape risk, according to state law.

Three recent high-profile breakouts from Pennsylvania county prisons each occurred less than 15 months after these mandatory inspections.

“These inspections are based on minimum regulatory requirements for operation and are not a security or vulnerability analysis,” Pennsylvania Department of Corrections spokesperson Maria Bivens told ABC News.

“This is a statewide and a national issue. And it’s not an issue with a quick fix,” Shubik-Richards said. “Hiring a quarter of your staffing complement doesn’t happen quickly. And training people to be professional prison guards is not something that just takes one week of a Zoom class. This is a highly nuanced, skilled, important community safety, community resilience position. So, it takes intention and investment.”

But Shubik-Richards said she believes there are steps that can be taken to lessen the risks of escape, one being the reduction of the number of people held in county jails for non-violent offenses or because of delays in getting a court date.

“You don’t need as many staff if you don’t have as many people in custody,” Shubik-Richards said. “During the pandemic, when we viewed prisons as a public health crisis … every county really worked hard to make sure that they were only detaining people who were really risks to public safety. In the last two years, the number of people in jail in Pennsylvania has started to grow again.”

She said the average citizen as well as policymakers don’t think of jails and prisons until there is a problem, like an escape.

“Many people in the public and many policymakers ignore prisons. They’re hidden, they’re closed and we forget about them. And we dismiss them,” Shubik-Richards said. “It is a shame that a really dangerous escape like [Cavalcante’s] is what it takes to pay attention to our jails.”