For the last 10 years, Helen Butler and a coalition of activists have tried to accomplish a near-impossible task: to closely monitor the monthly meetings of the local elections boards in each of Georgia’s 159 counties.

The meetings can be tedious. Officials often discuss the nitty-gritty details of elections that can influence how easy it is to cast a ballot, or a county might announce plans to close a polling place and change early voting locations.

“It’s a daunting task but we try to stay abreast,” said Butler, who leads a civil rights group called the Georgia Coalition for the People’s Agenda. “We miss some, I can tell you that. We don’t get every one.” When they can’t get to a meeting, they request meeting minutes, which can be spotty.

Before 2013, this kind of monitoring by activists wasn’t necessary. Georgia was one of nine states required to get any proposed changes to its elections approved by the federal government because of its history of racism and voting discrimination. The pre-clearance process meant that any change in voting – no matter how small – would have to be approved by the justice department before it went into effect to ensure it didn’t hurt minority communities. The Department of Justice would call community groups to find out how proposed changes would impact them, Butler said. Things didn’t fly under the radar.

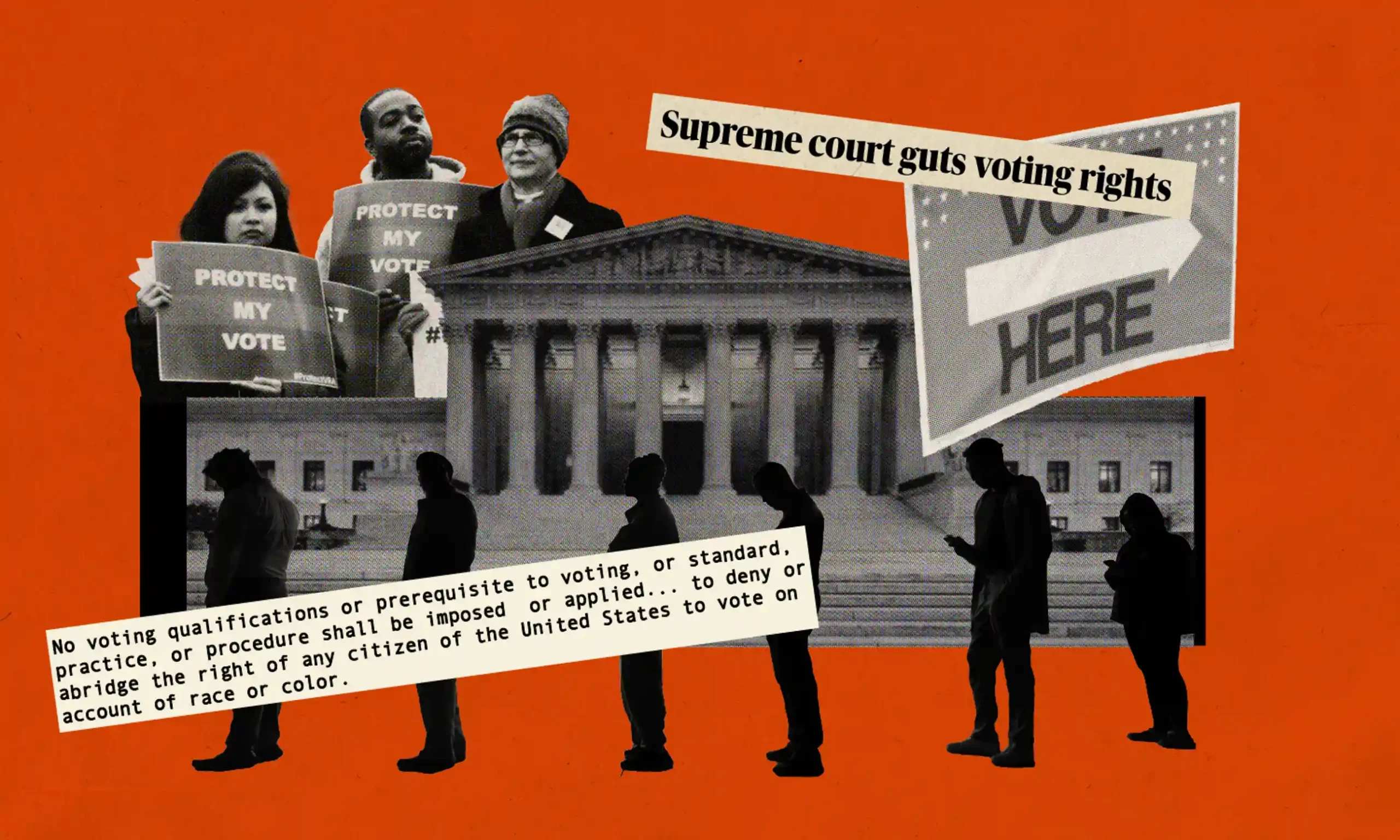

In 2013, the US supreme court gutted the pre-clearance requirement in a landmark case called Shelby county v Holder. In a 5-4 ruling, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that the Voting Rights Act’s formula used to determine which cities and states had to submit their election law changes was outdated and unnecessary. States like Georgia were now free to implement changes without federal government approval.

The decision unleashed a wave of voter suppression across the country. States once covered by section 5 pre-clearance have enacted new laws requiring voters to show ID, cutting early voting, making it harder to vote by mail, aggressively removing voters from the rolls and implementing maps that blunt the electoral power of Black and Hispanic voters. They have also closed polling places, forcing voters to travel long distances to cast ballots.

“The small changes are the ones that are deceptively suppressive,” said Nsé Ufot, a Georgia activist who started the meeting observation effort, called Georgia Peanut Gallery, in 2016 when she led the New Georgia Project.

In the last decade, the states and jurisdictions previously covered by section 5 have collectively passed at least 20 laws that restrict voting, according to data from the Voting Rights Lab, which tracks state legislation. Though there’s no way to know for certain whether the justice department would have rejected all of those laws, many included provisions previously blocked by the federal government.

Liz Avore, senior policy advisor for the Voting Rights Lab, also said there are clear trends among the types of laws passed after the Shelby decision, indicating that legislatures saw the ruling as an opening.

Five states pushed strict voter ID laws, for example, either leading up to or immediately after the Shelby decision.

And the ruling put activists at a severe informational and legal disadvantage. It cut away a safety net and replaced it with Whac-a-Mole, forcing groups like Butler’s to scramble to keep track of all the changes and then pick and choose where to bring costly and time-consuming legal challenges. Courts have been increasingly hesitant to embrace those challenges.

“For the groups that are on the ground, they have to be vigilant and they have to be the watchdog in ways that they may not have had to prior to the Shelby decision. They have to be the warning signal to litigators,” said Judith Browne Dianis, the executive director of the racial justice organization Advancement Project.

“If someone isn’t at the board of elections meeting, then nobody knows until it’s election time that, oh that polling place is closed and that was in a Black community or a Latino community and people now have to travel,” she said. “And by then it’s too late to fix it.”

The day of the Shelby county v Holder decision, Texas announced that a voter ID law, previously blocked by the justice department, would go into effect immediately. In North Carolina, a voter ID measure had been pending in the legislature, but once the decision was announced, Republicans expanded the measure to include a host of other new restrictions, including cuts to early voting. The US Court of Appeals would later say the measure targeted African Americans “with almost surgical precision.”

In Arizona, another state subject to pre-clearance, Republicans were able to pass a measure that had previously been halted. In 2011, lawmakers withdrew an effort to get people who collect more than 10 ballots to show ID after the justice department requested more information about its effects on Hispanic voters. In 2016, Arizona passed a law criminalizing ballot collection altogether. The Democratic National Committee challenged the law in court, but ultimately the supreme court upheld it in 2021.

The law has had real implications on voters – in 2022, a Latina woman from an Arizona border town spent a month in jail for collecting four ballots from her neighbors. People in her community say they worry about the chilling effect that the law and her prosecution has had on other potential voters.

There has been a blitz of new restrictions elsewhere since 2013. In Georgia, Republicans passed a 98-page law in 2021 that significantly changed voting in the state, requiring voters to provide ID when they request and return a mail-in ballot, limiting the availability of drop boxes and allowing any voter to bring any number of challenges against another voter. In Texas, Republicans also passed a sweeping measure in 2021 making it even harder to vote by mail.

The justice department sued states over the new laws in 2021, but neither case has gone to trial yet.

While pre-clearance was successful in stopping restrictive voting laws, one of the areas where it was most powerful was in redistricting – the process of redrawing electoral district lines every 10 years. Redistricting cases are some of the most complicated, lengthy and expensive lawsuits for voting organizations, so having the justice department review and block discriminatory maps before they went into effect was incredibly effective.

Nina Perales, a lawyer with Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund who specializes in redistricting, has long seen how state lawmakers have used the process to discriminate against minority voters in Texas. In every redistricting cycle since 1965, the courts had found that Texas discriminated against minority voters when it drew district lines.

When Texas redrew its maps in 2021, Perales again saw discrimination. Non-white voters drove 95% of the state’s population growth over the last decade, an increase that allowed the state to gain two additional seats in Congress. But when Texas redrew the lines, it reduced the number of congressional districts where minority voters comprise a majority.

Perales and the justice department quickly sued Texas over the maps last year, but the case has been slow to move towards trial. Texas has already had one election under maps alleged to be discriminatory.

The delay presents another hurdle for voting rights litigators. In a series of cases since 2006, the supreme court has rejected changes to voting rules if they come too close to an election. Without pre-clearance, states can drag their feet to draw a case out as close to an election as possible so that courts will not intervene.

Even with those obstacles in place, the redistricting cycle in 2021 – the first one to take place without the full protections of section 5 – yielded some surprising results.

Nicholas Stephanopoulos, a Harvard professor who specializes in voting rights, feared that states previously covered under section 5 would move aggressively to wipe out districts that gave minority voters the chance to elect candidates of their choosing. But when Stephanopoulos and two other scholars studied the maps that were passed in 2021, they found that the formerly covered states didn’t get rid of as many districts as they thought.

He speculated that could be because Republican-led states saw they could implement aggressive gerrymanders without dismantling majority-minority districts and were averse to the legal exposure.

“I think by and large the story is the dog that didn’t bark when it comes to redistricting,” he said. “There may have been a little retrogression, but there certainly was not widespread rampant retrogression which is what people like me and others feared in Shelby county.”

One could also argue, he said, that any amount of retrogression was too much.

When Roberts wrote the majority opinion in Shelby, he offered two balms for those concerned about a new wave of voter suppression. First, he wrote that section 2 of the law, which allows litigants to challenge voting laws that discriminate on the basis of race, was still in full effect.

But in 2021, the supreme court itself made it harder to bring section 2 cases outside of redistricting, upholding two Arizona voting restrictions including the limits on third-party ballot collection.

Earlier this year, many expected the supreme court would use a case challenging Alabama’s congressional districts to make it even harder to win section 2 redistricting cases. In a surprising move, the court ruled 5-4 to uphold section 2 as it currently exists.

Still, litigants bringing section 2 cases have prevailed in just 10 cases since 2010, resulting in the addition of just a handful of redrawn state legislative districts, Chief Justice John Roberts noted in his majority opinion on 8 June. And in section 2 cases, unlike section 5, the burden is on the challengers, not the state, to show why a voting practice is discriminatory – a high bar to meet.

Robert’s second balm was that Congress was free to update the formula it used to determine which states were covered. But Congress, too, has failed to push progress. In 2014, shortly after the Shelby decision, Representative Jim Sensenbrenner, a Wisconsin Republican, introduced a bill that would have required states that had five or more voting rights violations over a 15-year period to be subject to pre-clearance. The bill went nowhere.

When Democrats took control of Congress in 2021, there was renewed optimism that Democrats, backed by Biden, might be able to pass the bill. But it was ultimately stymied by Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, who refused to get rid of the filibuster, a senate rule requiring 60 votes required to advance most legislation.

Congress’ inaction, coupled with the supreme court’s rulings weakening the Voting Rights Act and the dozens of GOP-controlled state legislatures intent on passing voter suppression bills, leaves voters in a precarious position heading into the 2024 election. Voters across the country will be subjected to new voting restrictions, most of which states passed on the pretense of preventing voter fraud, encouraged by Donald Trump and others who continue to tout false claims. Voting advocates say it’s hard to imagine when the floodgates, opened by the Shelby county decision, might close.

“Voters are left with less protections as we move into the presidential election in 2024 at the same time as we have vote deniers,” Browne Dianis said. “It is this perfect storm.”