Thousands of low-income youths are working in violation of federal law and are struggling to complete school.

When Guatemalan immigrant Jose Velasquez was 13, he began spending his summers working alongside his mother in North Carolina’s tobacco fields.

“I worked 10 to 12 hours a day, five days a week in the Goldsboro area,” he told Truthout. “I had to get up at 4:30 am. A rusty van would come by, cram 20 or so people in, and take us to wherever we were needed. We were never told the destination in advance. I earned $7 an hour at first, but by the time I was 18, the pay went to $9.”

Velasquez also worked between 25 and 30 hours a week during the school year. “I had a job in an ice cream store and was paid $6 an hour in cash. The people who owned the shop knew I was undocumented,” he says. “They understood that I had to help my family.”

Velasquez admits that balancing work and school was difficult, but despite the pressure, he says that he was determined to excel. And he has. Now 21, he recently completed his second year as a scholarship student at Tufts University.

Nonetheless, he is concerned that the five summers he spent in the tobacco fields will eventually have a deleterious impact on his health since nicotine poisoning, called green tobacco sickness, is pervasive among leaf harvesters.

“No one cares about kids working in agriculture,” he says. “I worry about what will happen to my body when I’m 40 or 50.”

It’s a pressing concern not only for Velasquez, but also for the approximately 500,000 kids under the age of 18 in the U.S. who plant, pick and package our crops, all of it legal due to a loophole in the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). Under the act, young farm laborers (as well as domestic workers and door-to-door salespeople) are denied the protections afforded to other school-aged children.

But even the full range of legal protections do not bar children from working: Under FLSA, non-farmworker children under the age of 14 can only work as actors, newspaper deliverers or babysitters, although they can also work in family businesses as long as their tasks do not put them in harm’s way. Fourteen- and 15-year-olds are permitted to work three hours a day — up to 18 hours a week — when school is in session as long as the job does not expose them to toxic chemicals or send them into industrial settings or mines. Then, at 16, these restrictions fade and a teen can work an unlimited number of hours as long as the job does not involve dangerous chemicals or send them underground.

But even these minimal protective laws are often flouted. Not only are thousands of kids working longer hours in dangerous occupations, but their numbers are growing; researchers report that the number of kids employed in violation of child labor laws spiked by 37 percent in 2022 — and by 283 percent since 2015.

Republican lawmakers seem unfazed by this, and in at least 10 states — Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin — they are now trying to erode FLSA protections even further. In fact, nearly a century after its passage, dozens of lawmakers have introduced legislation to scale back these basic protections.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, one of the most egregious rollbacks was recently signed into law by Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders.

Under the provision, 14-year-olds will be able to work in meat coolers and industrial laundries; 15-year-olds will be able to work on assembly lines; and 16- and 17-year-olds will be able to serve alcohol. Proponents of the measure included Americans for Prosperity, the National Restaurant Association and the National Federation of Independent Business.

Pending measures in other states are equally egregious and include an Ohio bill to allow teenagers to work until 9 pm on school nights (two hours later than allowed under the FLSA); a Minnesota bill to allow 16- and 17-year-olds to work in construction; and a New Jersey bill to permit 16- and 17-year-olds to work 50 hours a week during school breaks. SB 542, pending in Iowa, will, if signed by the governor, allow 14-year-olds to work up to six hours a day and will permit 16-year-olds and 17-year-olds to work the same hours as adults. In addition, a special committee is being established to determine the pros and cons of granting driver’s licenses to 14-year-olds.

“State bills to expand the hours and places kids can work may sound innocuous at first glance, but research shows that school completion and grades drop when kids work long hours,” Reid Maki, coordinator of the Child Labor Coalition, a 34-year-old project of the National Consumers League, told Truthout. “Students who work more than 20 hours per week almost always see a decrease in academic performance.”

Unfortunately, he continues, many students have no choice but to work full- or almost-full-time while enrolled in school. Their situations vary: While an estimated 130,000 migrant children entered the U.S. shelter system as unaccompanied minors in 2022, others are born in the U.S. but have been forced by circumstances beyond their control to live away from their families. Still others live with friends or relatives but have to help with expenses.

Jean Bruggeman is executive director of Freedom Network USA, a human rights group that brings trafficking survivors, legal and social service providers, advocates and researchers together to push for anti-racist, non-punitive policy measures to benefit survivors. She told Truthout that there is a “grey zone” that makes it difficult to assess exploited children. “Are these kids living in such desperate poverty that they’re forced to work long hours in dangerous jobs to help their families, or are they being trafficked?” Bruggeman asks. “Homeless minors often engage in survival sex to have a place to sleep other than the street. They may be trafficking victims, but they usually do not want to report it because they will be sent to child welfare.”

Until we change the way we support youth, she continues, current policies will continue to allow the conditions for child trafficking and labor exploitation to flourish. “When we refuse to feed kids, when we refuse to give them a safe place to live or provide them with the chance to go to a school where they can get counseling and medical care that goes beyond a nurse giving out a Band-Aid, we’re making it possible for them to be taken advantage of,” she says.

The problem of child labor, she continues, is rooted in poverty, and when government policies take a punitive approach — deporting people who are undocumented, refusing to grant asylum to those fleeing persecution or violence, or arresting people with substance abuse disorders — it allows trafficking and exploitation to spread and fester.

Melissa Hope Ditmore, author of Unbroken Chains: The Hidden Role of Human Trafficking in the American Economy, agrees with Bruggeman, but adds that the issue typically involves people who prey on others. “Kids who come from El Salvador, Honduras or Guatemala do not find their way to Iowa by accident,” she says. “They either know someone who is already there, perhaps a family member or someone from their hometown who agrees to be their sponsor, or they’re offered a job by someone — a middleman — who has a vehicle and says that he’ll take them to a farm, factory, or other worksite. Sometimes these middlemen hang out at children’s detention facilities or immigration holding centers and recruit people the minute they’re released. The vast majority of kids drop out of school; even if the sponsor promises to enroll them, they don’t always follow through.”

In addition, Ditmore says, recent arrivals are often told that they owe money to the person who helped them get to the U.S, got them a job or gave them false papers. “Most people want to be honorable, and even if they suspect that the debt is bogus, they want to be free of it,” she explains. “They may not be in actual debt bondage, but they may fear that they or their families will be harmed if they don’t pay. There is no safety net for these kids, and it is not uncommon for them to go hungry or fall in with people who exploit them. Going to school may not even be on their radar.”

Despite this, many teachers and school administrators attempt to do everything they can to assist the students who find their way into their classrooms.

Schools Can Play a Critical Role — If Kids Enroll

Lara Evangelista is the executive director of the Internationals Network for Public Schools, 31 affiliated public schools and academies in California, Kentucky, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Virginia and Washington, D.C. that are tailored to the needs of new immigrants who do not yet speak English. The network’s 10,000 students come from 130 countries and speak more than 100 languages, Evangelista told Truthout. “Ever since the network opened its first school in 1985, we’ve tried to be a safe haven,” she explains.

Students, she continues, often have to run to work after school and sometimes have to work before the school day begins. “They sometimes find it hard to do homework or stay awake in class. Our teachers and staff try to design curricula around their needs and give them opportunities to complete assignments during the school day. We’re flexible. We know that high school completion may take five or six years, so we allow students to remain enrolled until they’re 22 [in New York City].” She added that in some other locations outside of New York City there are district rules that force the schools to impose a younger age limit, but that their schools always allow students to stay until the maximum age allowable by the district.

Network schools, she adds, also work to address students’ social and emotional needs and recognize the resilience and skills they bring into the classroom. At the same time, she says, “We know that they miss some typical high school experiences because of their circumstances.” Nonetheless, Evangelista acknowledges that most young immigrants do not attend network schools — many of those who attend school opt to go to other programs in their communities — but says that because the network works exclusively with refugees and asylees, it can tailor curricula and programming to them in ways that other public programs cannot.

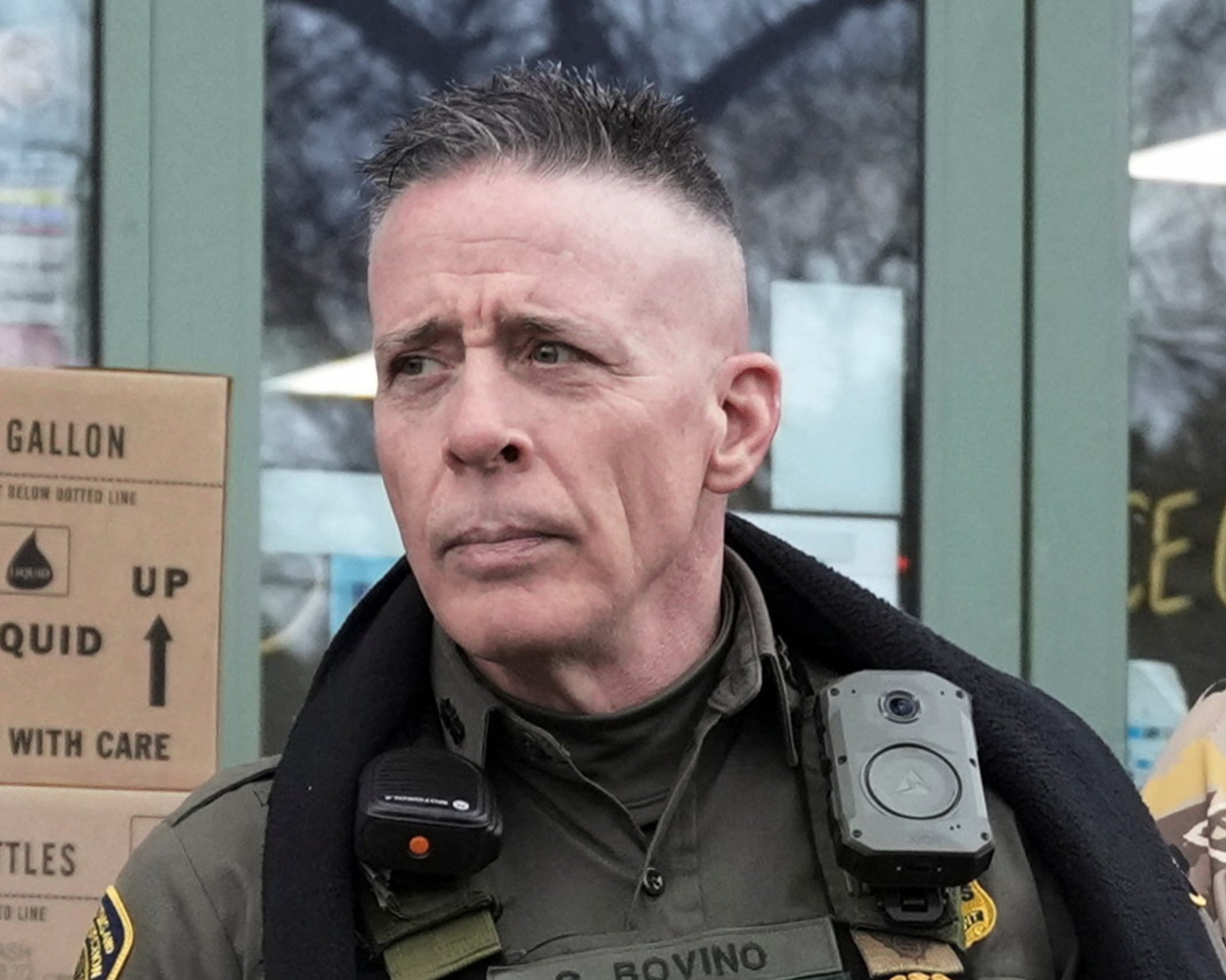

The goal, of course, is keeping new arrivals in school, and like other advocates, Evangelista is encouraged by the recent introduction of several bills that will crack down on labor violators and rein in child exploitation. What’s more, she is encouraged that over the past two years, the Department of Labor has ramped up inspections and levied fines against more than 450 offenders across the country. Those nabbed include the Villa Roma Resort and Conference Center and Villa Resort Lodges in Callicoon, New York, where 11 children — 14- and 15-year-olds — were found working longer and later than allowed by federal law.

Moreover, throughout the country, minors have been found working in slaughterhouses, construction sites, laundries, restaurants, garment factories, auto plants and delivery services in violation of the FLSA. Violators include industries as varied as Hearthside Foods, Hyundai, McDonalds and J. Crew. Some of the fines have been significant. For instance, Packers Sanitation Services, Inc. (PSSI), a company owned by Blackstone Private Equity, was fined $1.5 million by the Department of Labor in February for providing 102 cleaners between the ages of 13 and 17 to more than a dozen Midwestern meatpacking plants.

Labor and child welfare advocates see this as a good start.

“Our focus is combating illegal child labor across all sectors,” Solicitor of Labor Seema Nanda told Truthout by email. “Given the increase of illegal child labor since 2018, the department is laser focused on improving processes, capacity and authority to protect children. That’s why we recently launched an Interagency Task Force on Child Labor and why we have called on Congress to give the department better tools to hold companies accountable for putting children in danger.”

It won’t be easy.

As entertainer-activist Ashley Judd noted in a March editorial in USA Today, “Americans thought child labor was a travesty ‘over there.’ That myth has been shattered,” she wrote. Judd also pointed out that in 1978, each labor inspector was responsible for monitoring 69,000 workers. Forty years later, in 2018, they were expected to monitor 175,000. “Labor trafficking in general and child labor in particular can flourish only when greedy, unscrupulous employers are not held accountable,” she wrote.

Efforts are underway to make this happen.

Several bills meant to make enforcement more robust — and hold employers to account — are in the pipeline: The Children Don’t Belong on Tobacco Farms Act would amend the FLSA to prohibit kids like Jose Velasquez from having direct contact with tobacco leaves until they are at least 18. A second bill, called the CARE Act, would amend the FLSA to extend the same wage and hour protections to all minors, regardless of whether they work in agriculture, domestic labor, or other occupations. Lastly, the Combating Child Labor Act would increase civil penalties from the current maximum of $15,138 per violation to $150,000. The bill also imposes, for the first time, a minimum fine of $1,000.

Advocates like Maki would also like to see a change in the way farmworkers are paid. “People who pick crops are paid by the bucket,” Maki told Truthout. “Each bucket weighs about 45 pounds and the more buckets you fill, the more you earn. It encourages risk taking. It’s inhumane. If adults were paid an adequate hourly rate, it would make an enormous difference, and families would be able to keep their kids in school. If they ended the piece rate, I believe child labor on farms would be reduced or even disappear.”

For many activists and advocates, ensuring adequate wages is imperative if we are going to end child labor and ensure that kids can get the education they deserve. “When children have to work long hours to support themselves, they usually don’t get enough sleep, or may have interrupted sleep,” Bruggeman says. “They may be malnourished. They may have been injured on the job or they may be dealing with trauma, abuse or exploitation. All of this impacts schooling. If we want to support youth, see them finish school, we have to give them material aid. Everyone says they want to protect children from labor exploitation but … until we eliminate poverty, we are not really addressing the problem.”