A Mississippi police officer shoots an 11-year-old boy who dialed 911 to report a domestic disturbance.

Attorneys file a lawsuit on behalf of a Georgia woman who died after calling 911 for mental health help and falling out of a moving police car while handcuffed.

A New Jersey police officer is charged with manslaughter in the fatal shooting of a man who called 911 to report an armed trespasser. The man was still on the phone with a dispatcher when he was shot in his front yard.

The slew of cases this week renews questions about who should respond to emergency calls — and what needs to change to prevent pleas for help from turning deadly.

“When residents call 911 for service, they are concerned, they need assistance, they seek protection — and they trust the officers responding to their calls will respond accordingly and help them,” New Jersey Attorney General Matthew Platkin said in a statement. “Tragically, that did not happen here.”

While each of the cases in Mississippi, Georgia and New Jersey has unique circumstances, the outcomes in each come down to issues of police hiring, training, policy and accountability, said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum.

“When you look at each case, each one inevitably makes you step back and ask, how could this happen?” Wexler said.

How often do police injure, kill people who call 911?

Policing fatality data is notoriously poor, and the data that is collected is not granular enough to capture how often police injure or kill someone who calls 911, said Jorge Camacho, policy director of the Justice Collaboratory, a research center at Yale Law School.

Get the Daily Briefing newsletter in your inbox.

The day’s top stories, from sports to movies to politics to world events.

A Washington Post database of all fatal police shootings — not just people who call 911 — suggests police have fatally shot more than 8,500 people since 2015, with Black Americans shot at a disproportionate rate. Police killed the highest number of people on record last year, according to the database.

“The federal government has over the years attempted to collect information on use of force, deadly incidents involving policing, police-involved shootings, and they’ve never really succeeded in pulling it off,” Camacho said. “By their own best estimates, they tend to under count the number of police-involved deaths by 50%.”

A Mantua police officer examines the scene of the fatal police shooting of Charles Sharp III in September 2021.

What happened in Georgia, New Jersey, Mississippi?

In Mantua, New Jersey, a police officer shot Charles Sharp III, 49, who called 911 to report two burglars in his rear yard, one armed with a gun. An investigation by the state’s Office of Public Integrity and Accountability found fewer than five seconds elapsed between when the officer stepped from his police vehicle and when he began shooting at Sharp. A replica gun was found near Sharp, according to an account from the Attorney General’s Office.

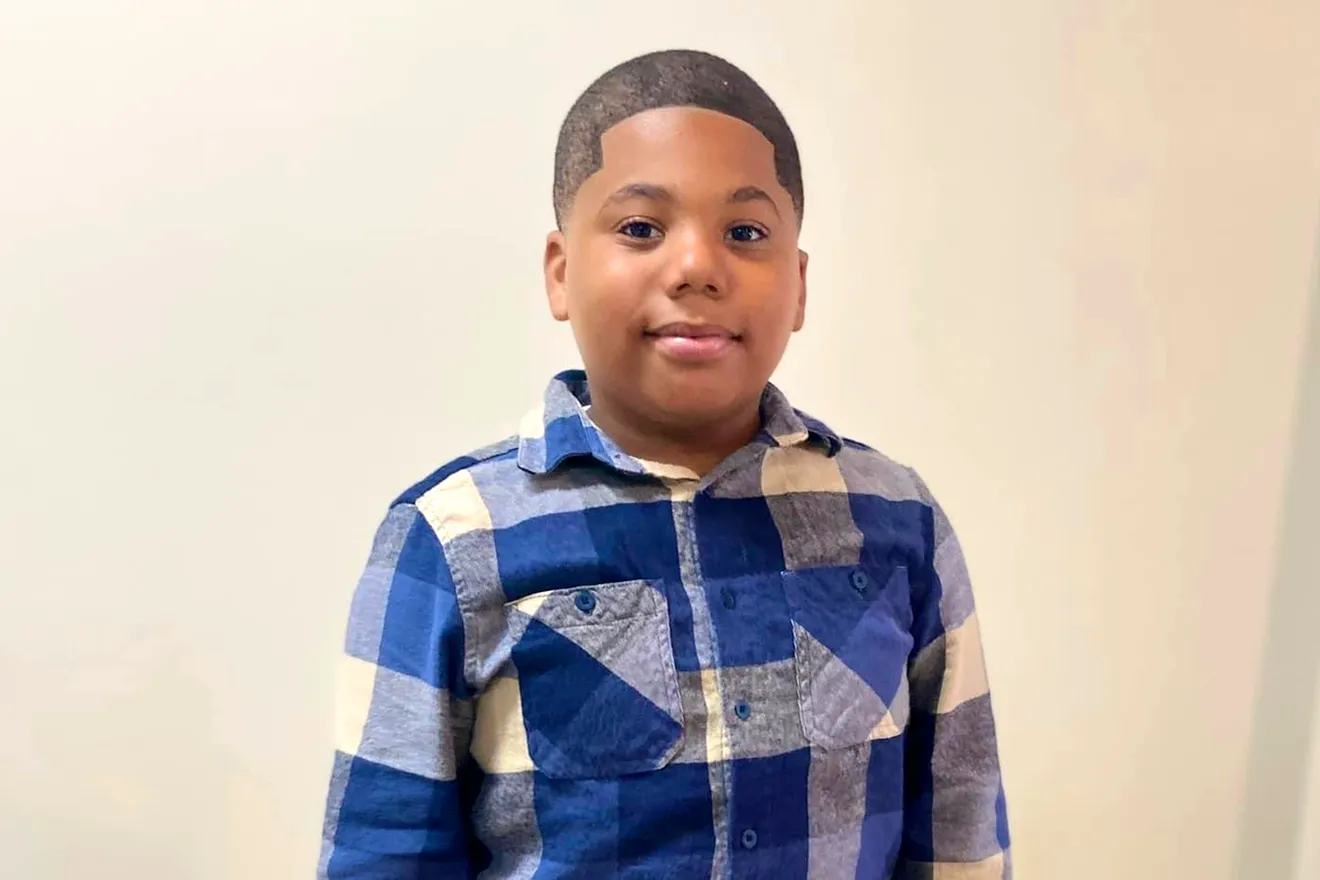

In Indianola, Mississippi, an officer shot Aderrien Murry, 11, in the chest at the boy’s home about 100 miles northwest of Jackson, according to the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation. The boy’s mother, Nakala Murry, told CNN she asked the boy to call the police after the father of another one of her children arrived at the home “irate.”

Murry told the outlet an officer who arrived “had his gun drawn at the front door and asked those inside the home to come outside.” Aderrien’s mom said he was shot “coming around the corner of a hallway, into the living room.” He was recovering following his release from the hospital, his attorney said Thursday.

This undated photo provided by Nakala Murry of Indianola, Miss., shows her 11-year-old son Aderrien Murry, who was shot and wounded by an Indianola Police Department officer on Saturday, May 20, 2023, during a domestic disturbance call at the home of Murry’s family. The Mississippi Bureau of Investigation is examining the shooting.

In these cases, it appears officers arrived on the scene and acted too quickly, Wexler said. His organization is currently rolling out training across the country on de-escalation techniques, with a focus on helping officers gather as much information as possible before arriving on a scene.

“The conventional thinking was the most important thing is to get to a location as fast as you can, and to get to the caller as quickly as you can. In some cases, when it’s life or death situations, that makes sense,” Wexler said. “In other cases, we now teach to slow things down. Have a plan. Use information. Use time and distance.”

Information relayed to officers responding to 911 calls can often be vague or inaccurate, such as a burglary in progress at a given location, Camacho said. With little information, officers go into a hyper-vigilant state, he said.

“Officers have historically been trained and trained and trained to be hyper-vigilant about their own safety, and about the fact that violence can occur at anytime, and that deadly violence can be used against them at anytime,” Camacho said.

That’s why more efforts are now focusing on training dispatchers, he said. If the officer in New Jersey had been given a description of the suspects and the homeowner, the tragic shooting may have been avoided, he said.

In the case of Brianna Grier, a 28-year-old mother of twin girls, attorneys for the family say she was having a mental health crisis when she called 911 for help at her parents’ home in Sparta, about 70 miles east of Atlanta. Grier had diagnosed schizophrenia and asked the operator for help getting medicine, the civil suit says.

Instead, members of the Hancock County Sheriff’s Office arrested Grier and put her in the back seat of the patrol car, handcuffed with no seatbelt on, according to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. She fell out of the open door of the moving car and hit her head on the road, the civil suit says. She suffered brain trauma and died six days later.

“That just seemed like incompetence,” Camacho said. “It highlights how vulnerable you are as someone who’s been arrested in handcuffs.”

Marvin Grier holds a program during a funeral service for his daughter Brianna Grier on Aug. 11, 2022, in Atlanta.

The case also underscores how many officers are not equipped to respond to mental health emergencies, Camacho said.

Christopher Mercado, a retired NYPD lieutenant and an adjunct assistant professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City, called the case “extremely disturbing.”

“There were several breakdowns in not only policy and procedure, but also leadership,” he said.