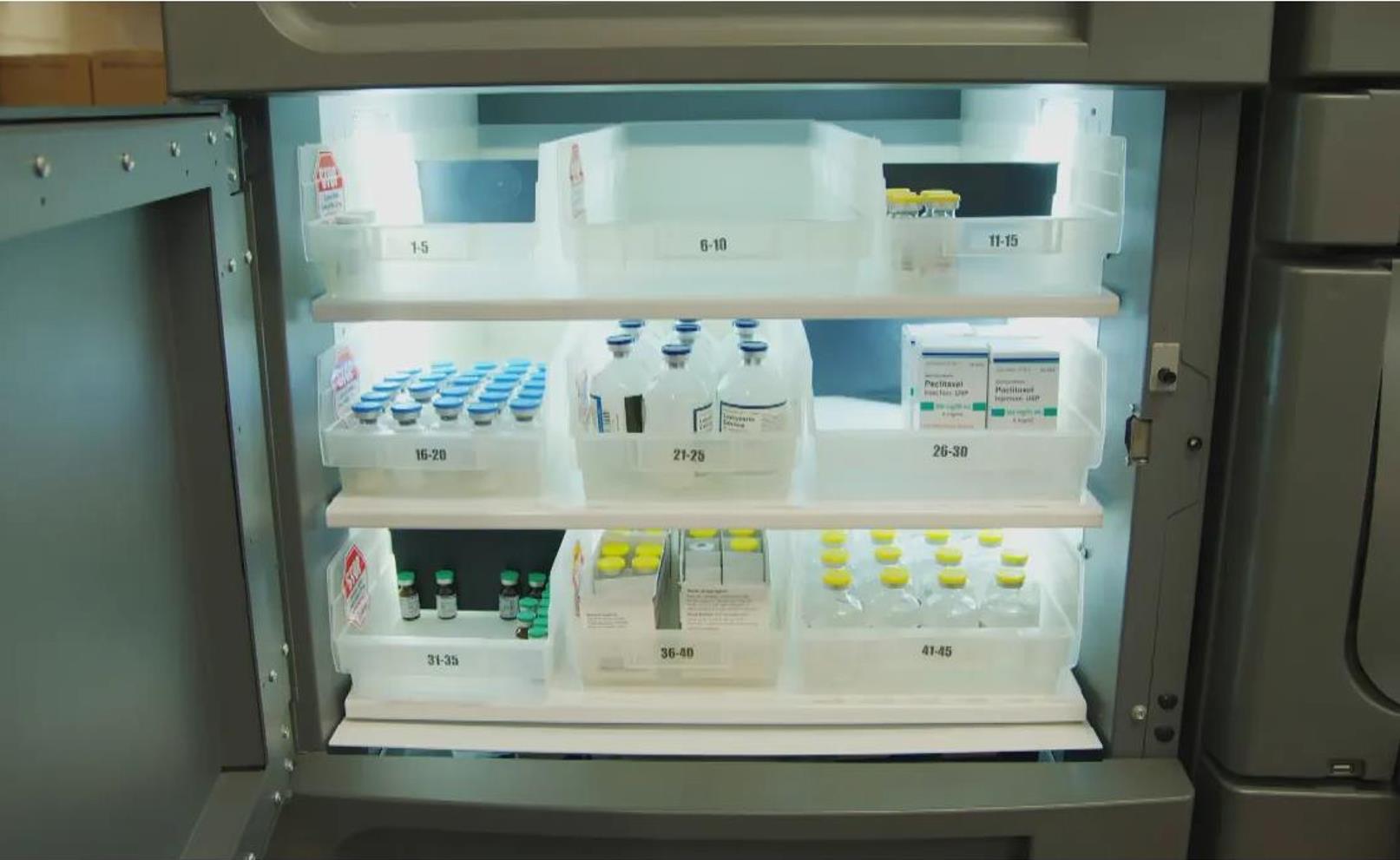

Fourteen cancer drugs are in shortage, according to the Food and Drug Administration.

Widespread shortages of cancer drugs are forcing doctors to make difficult decisions about how to treat their patients, including rationing doses and turning to other treatment options with potentially more side effects.

As of Wednesday, the Food and Drug Administration listed 14 cancer drugs in shortage.

“The oncology shortage is especially critical,” FDA Commissioner Dr. Robert Califf told NBC News. “I’m a former intensivist doctor and I’m very aware of the consequences if you can’t get needed chemotherapy.”

According to a March report from the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, drug shortages are at record highs. New drug shortages increased by nearly 30% between 2021 and 2022. By the end of 2022, there was a record five-year high of 295 active drug shortages.

“I don’t know of a time that’s worse than this,” said Dr. Julie Gralow, the chief medical officer and executive vice president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. “What’s different about this shortage is, I think, it’s just the broad applicability of these drugs, how important they are, you know, globally, in the U.S., in the treatment of many diseases.”

Among the drugs in shortage is carboplatin, a chemotherapy agent used as a first-line treatment for a number of cancers.

“Carboplatin is such an important drug for the treatment of many cancers — breast cancer, ovarian, head and neck, lung cancer, among several others,” said Dr. Lucio Gordan, a medical oncologist and president of Florida Cancer Specialists and Research Institute, a network of cancer clinics. Gordan said they were completely out of the drug for nearly two weeks.

“I’ve been doing this for 20-plus years. This is the worst I’ve ever seen,” he said.

Florida Cancer Specialists knew that the shortage was coming and tried to prepare. For the last couple of months, they’ve been rationing by rounding down doses of carboplatin by 10%, which Gordan said doesn’t diminish the drug’s efficacy.

“We have been rounding down for a while,” he said. “But we just ran out of the drugs, so there’s nothing to be rounded.”

Carrie Cherkinsky, 41, of Tallahassee, Florida, learned of the shortage from a Facebook support group for women with ovarian cancer. Even so, she was shocked to learn that she wouldn’t be able to get her second round of chemotherapy, scheduled for May 15, at Florida Cancer Specialists. Gordan was not involved with her care.

“Who’s going to be held accountable for this?” said Cherkinsky, who was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in March. “For me not getting the lifesaving treatment?”

Carboplatin isn’t just an effective drug; it’s also less toxic and causes fewer side effects than other available drugs.

“One of the issues though with these alternative medications is often they’re not as good, so it may compromise survival outcomes,” said Dr. Angeles Alvarez Secord, president of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

In addition, “when there’s more toxicity, there’s more cost to the treatment because you’re also dealing with the side effects, or giving additional drugs to try to prevent the side effects,” Secord said. “So the alternatives often, even though they’re present, are still not meeting the best standard of care.”

Nationwide, hospitals and cancer centers have been forced to make similar decisions when it comes to cancer care.

According to a May survey conducted by the Society of Gynecologic Oncology, doctors in at least 40 states have at least one chemotherapy drug in shortage.

Dr. Eleonora Teplinsky, a breast and gynecologic medical oncologist at Valley Health System in New Jersey, said the shortages are devastating.

“Cancer is life-changing as it is but you expect as a patient that you’re going to walk into an office and be given the very best that exists,” Teplinsky said. “And right now we don’t have the very best to give in certain cancers.”

Drug shortages cause extra stress not only for cancer patients, but for medical providers as well. On top of being in a workforce that’s already burned out and exhausted from a pandemic, doctors have to scramble to find lifesaving treatments.

“All the practices in the country, not only in oncology, we have been stressed out much more since Covid,” Gordan said. “This is another curveball that impedes us to do the best we can.”

Shortages can sometimes catch providers off guard.

Suppliers don’t give warning when a drug is about to be in shortage; they’ll just stop filling all of their orders, said Andrea Iannucci, the assistant chief pharmacist at UC Davis Health. “So we place an order, and we think it’s going to arrive and it doesn’t, because the drug was unavailable,” Iannucci said.

Keri Carvill, 44, of Sacramento, California, was diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer in March but wasn’t able to get her first dose of carboplatin until May 19. Triple-negative breast cancer is a particularly aggressive form of the disease.

“It’s stressful and scary,” Carvill said.

What led to the shortage and what can fix it?

The current carboplatin shortage was caused in part by quality concerns at one manufacturing facility, Intas Pharmaceuticals, in India, but experts say the real problem is more chronic.

“Unfortunately, the profitability of this industry is very low or nonexistent,” Califf said. “A number of firms are going either out of business, or they’re having quality problems because of difficulty investing in their technology. That’s the core underlying reason for the shortage that we’re seeing.”

In a statement to NBC News, Intas Pharmaceuticals said it is working with the FDA to release existing inventory of carboplatin and other medically necessary products. It is also working with the agency on a plan to resume manufacturing, but added that a date has not yet been confirmed for when that will happen.

Califf said the FDA is working with additional manufacturers to make more carboplatin available.

Long-term solutions, however, are going to require “intervention by Congress and the White House in order to get this industry in the right place,” he said, adding that a White House team has been working on the drug shortage issue.

Teplinsky, the oncologist in New Jersey, said she’s been encouraging her social media followers to reach out to elected officials to advocate for timely production of chemotherapy drugs and long-term policies to ensure this doesn’t happen again.

“Delaying care impacts outcomes,” Teplinsky said. “And so in this case, either we can’t give people what they need, or we have to wait, which we know will lead to negative consequences.”