Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) signed into law Tuesday a sweeping ban on sustainable investing.

House Bill 3 bars state and local governments from factoring in environmental, social or governance (ESG) factors in their decision of whether to invest or contract with specific businesses.

It also obligates state-registered banks to make loans to several industries — including fossil fuels, private prisons or the manufacture and sale of firearms — that the GOP alleges some large financial firms have been turning away from.

House Bill 3 would bar financial institutions from “discriminating against customers for their religious, political, or social beliefs — including their support for securing the border, owning a firearm, and increasing our energy independence,” according to a fact sheet from the state of Florida.

In his signing ceremony on Tuesday, DeSantis — standing above a lectern that said GOVERNMENT OF LAWS, NOT WOKE POLITICS — lambasted ESG as an attempt by “Davos elites” to “impose ideology through business institutions.”

“They want to use economic power to impose this agenda on our society,” DeSantis said Tuesday.

“And we think in Florida, that is not gonna fly here.”

But financial experts told The Hill that the bill is likely “a political stunt” with little practical impact.

“It prohibits ‘banks that engage in corporate activism,’” Shivaram Rajgopal, a professor at Columbia Business School, told The Hill.

“But what does that even mean? Legally, that’s going to be difficult to define,” he said. “Should banks not get involved if a manager is simply a bad manager, and wastes shareholder capital?”

The anti-ESG bill was largely political “with little practical effect beyond limiting Florida’s future investment options,” Brandon Owens, vice president of sustainability at consulting firm Insight Sourcing Group, told The Hill.

DeSantis’s anti-ESG turn has not been an especially popular strategy nationwide — he trails his presumed 2024 presidential rival, former President Trump, by 36 points, according to a new poll.

But the Florida governor has sought to cast himself as leader amid a larger push by national and state GOP lawmakers to crackdown on ESG investing.

DeSantis in February published a book that sought to make the movement against “woke capital” a key part of his bid for a national platform — and potentially the presidency.

In March, 19 GOP governors, including DeSantis, released a statement calling ESG a “direct threat to the American economy, individual economic freedom, and our way of life.”

The anti-ESG movement in March led to President Biden’s first veto — overturning a bill that would have barred pension fund managers from considering factors like climate change in making investment decisions.

On Tuesday, Florida GOP leaders framed the bill as necessary to keep small businesses from being unfairly denied access to loans.

DeSantis was joined at the event by the owner of Sovereign Ammo, which lists itself as a “proudly Conservative company with Patriotic values of God, Guns, and Family.”

Another such firm is private prison operator GEO Group, which DeSantis name-checked in February when he announced the bill, according to Florida Politics.

The Boca Raton-based company donated $740,000 to the Republican Governors Association, which itself put $14 million into DeSantis’s campaign coffers in 2022, according to investigative journalist Jason Garcia.

Two GEO Group employees also gave DeSantis’s PAC about $100,000 in 2018, according to the Orlando Weekly.

The company has been in legal trouble for years. In 2021, for example, GEO Group was required to pay $17 million in back pay to detainees at an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facility it ran in Washington state — people who were paid $1 a day, which a federal jury found to be a violation of minimum wage laws.

Another lawsuit filed in March accuses the private prison operator of using toxic chemicals to clean a California ICE prison — and continued to do so despite prisoner complaints that it was irritating their skin and causing them to bleed from their noses and mouths.

But as GOP leaders told it, the company’s woes are political in nature.

The private prison operator, which for years has struggled to get investment, was “de-banked” because “they were contracting with the actual federal government” on immigration enforcement, DeSantis said at the time.

In the ceremony on Tuesday, Florida state House Speaker Paul Renner (R) argued that only political factors had kept the private prison industry from getting investment.

Renner laid out a scenario in which a private prison company goes to the financial side of a bank: “They look and say you’re a bankable client because your clients are the state governments and the federal governments. Of course, you’re an easy lending decision.”

“And they set them out, rejecting them, and putting them into bankruptcy.”

But this idea of being excluded increasingly relies on obsolete ideas of what sustainable investing is, Owens of Insight Group wrote to The Hill.

First, “the animating concept behind this legislation—namely, that ESG investing is a drag on profitability—is simply not true,” Owens said.

But more and more often, sustainability isn’t something that the financial industry treats separately from profit.

Instead, it is becoming an essential part of profit, he said — and one that is increasingly folded into a far more traditional concept: risk.

In sustainability thinking, generally “protecting the environment must be factored in because failure to do so will result in the destruction of our environment and, therefore, end profits,” he wrote.

That concept could swallow the whole law, he said. If environmental risks start getting priced into risks in general, “the Florida law will become ineffective as ESG is subsumed” into more granular financial questions.

The director of the nation’s first sustainability bank — based in Saint Petersburg, Fla. — said the bill could chase his bank out of the state.

Climate First Bank boasts of its position as the first FDIC-insured community bank dedicated to investment in the environment and sustainability.

The list of companies it won’t do business with maps closely to the ones House Bill 3 aims to protect, CEO Ken LaRoe said.

“We won’t do business with for-profit prisons, guns, porn, bad agriculture, dirty energy, or extractive industry,” he said. “And they put our exact exclusionary list in the bill.”

If he stays chartered in the state, every year starting on July 1, LaRoe will have to sign an affidavit swearing he hasn’t discriminated against those industries.

That means, at a start, that the exclusionary list will have to go.

Beyond that, if he has to invest in industries that he considers risky, “We’ll price it appropriately,” LaRoe said.

“And if they choose to bank with us? We’ll take their dirty money and use it to do something good.“

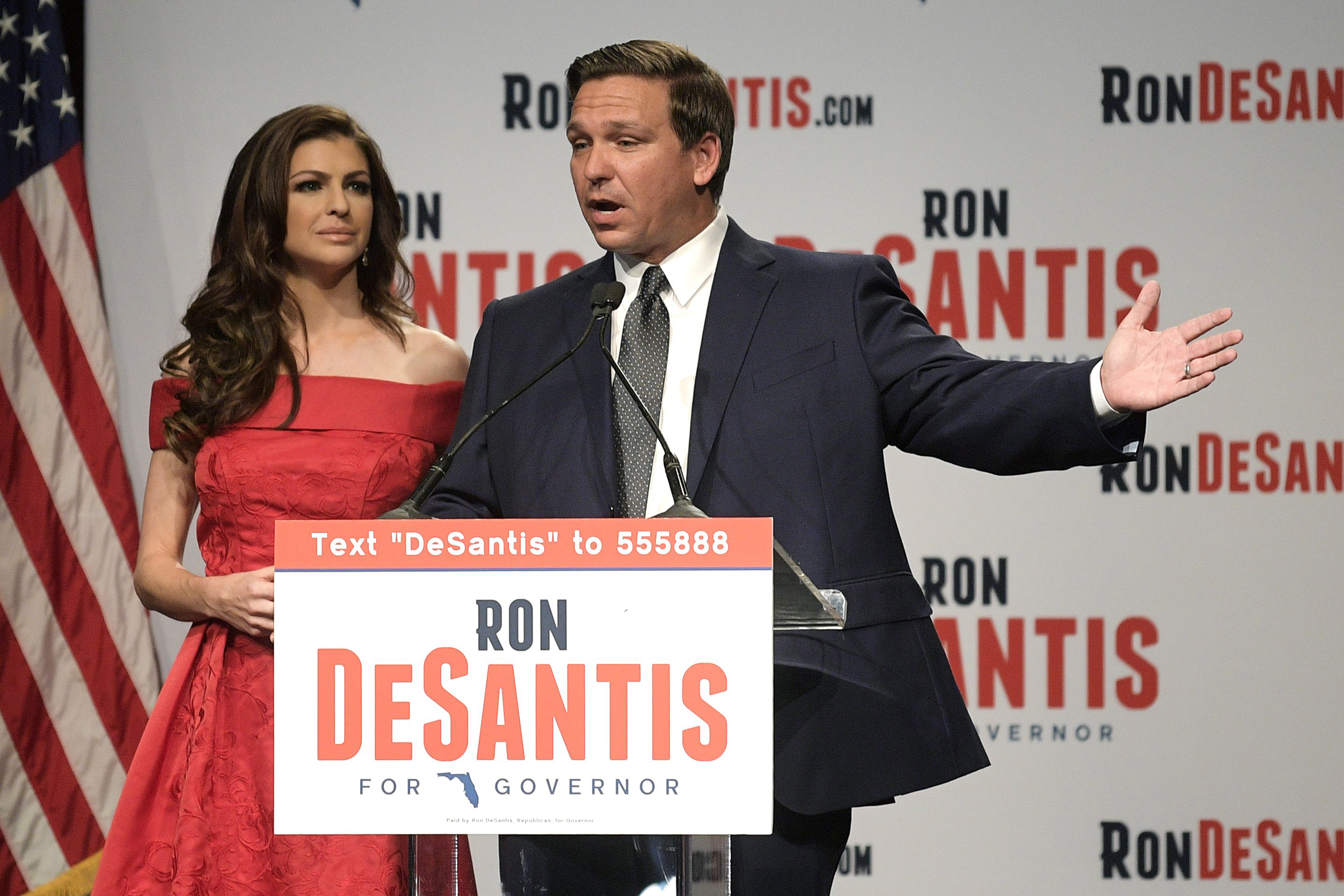

DeSantis signs bill targeting ‘discriminatory ESG’ in Florida