WASHINGTON — Before Joe Biden opted against running for president in 2016, one of his closest advisers laid out what a bid would have looked like: rooted in “his burning conviction that we need to fundamentally change the balance in our economy and the political structure to restore the ability of the middle class to get ahead.”

“An optimistic campaign. A campaign from the heart. A campaign consistent with his values, our values, and the values of the American people,” Ted Kaufman wrote in 2015 about the then-vice president’s potential run.

After Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton to win the White House, in part by peeling off disaffected Democrats in the so-called blue wall of industrial battleground states, Biden explained to this reporter why he had seen it coming.

He was careful to blame not Clinton but rather the Democratic Party more broadly, saying there was an “elitism that’s crept in” to its thinking that neglected what he long considered Democrats’ base of support, especially middle-class union voters.

“I thought we constantly made a mistake of not speaking to the fears, aspirations, concerns of middle-class people,” Biden said then. “You didn’t hear a word about that husband and wife working, making 100,000 bucks a year, two kids, struggling and scared to death. They used to be our constituency.”

Biden set about fixing that “mistake” with his 2020 bid, promising to improve the lives of “the backbone of the country, the middle class,” over and over in stump speeches. But the election was dominated by Trump and Covid and the intersection of the two, even as advisers credit Biden’s economic message in his rebuilding of that blue wall, having won back Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

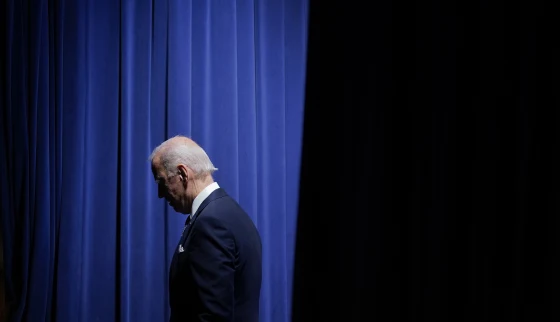

Interviews with more than a half-dozen advisers and close aides ahead of his re-election announcement Tuesday offer insight into how Biden, who is 80, views what’s most likely to be his last campaign: a chance to see through an economic vision for the country and his party that guided his first bid for public office a half-century ago.

“It’s always been important to him,” Ron Klain, Biden’s former chief of staff and a longtime adviser, said in an interview about Biden’s focus on the middle class. “It was important to him in 1988. It was important to him when he ran in 2008. It was important when he thought about 2016. It was important to his campaign in 2020. … And it’s important to him as president, most importantly. And it’ll be important to him in a second term.”

Biden plans to run the campaign Kaufman described in 2016 and the one that was overshadowed in 2020, those top aides and advisers said in interviews. But Tuesday’s announcement video made plain that some of the other forces that crowded out that economic message in 2020 are still top of mind — if not Trump himself, Trumpism. Scenes from the Jan. 6 insurrection are set against Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris, as Biden says “MAGA extremists” in the Republican Party are out to undermine the social safety net as well as “bedrock freedoms.”

“The question we are facing is whether in the years ahead we have more freedom or less freedom. More rights or fewer,” Biden says.

Unlike Biden’s 2020 launch video, Trump is not named, and only briefly pictured — standing with his potential chief challenger, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis. Even if 2024 isn’t a rematch of the last election, advisers have long argued that any Republican who defeats Trump for the nomination will have done so by adhering to a Trump-style approach — particularly as it relates to the nation’s democratic institutions.

“I think it’s fair to say he saved democracy,” a Biden adviser said of his 2020 victory. “In ’22, it was really put to the test — it was being put to the test more than people thought at the time. And I think ’24 it’s going to be put to the test again. And the thing about it is, you gotta win every round.”

Biden, in the video, declares it is time to “finish the job,” a reference to the domestic agenda advisers see as key to winning the next round and for the party more broadly. For someone who has always considered himself a loyal Democrat, Biden has relished challenging his party when he sees fit and defying conventional labels as progressive, moderate or centrist. Four years ago, when he was asked where he fit on the ideological spectrum, he would answer that he’s an “Obama-Biden Democrat.” Now, what it means to just be a Biden Democrat is coming into clearer focus.

Aides and advisers suggest that for Biden, the 2024 race is an opportunity to prove that despite his age, his view of the future of the Democratic Party — one based less on ideology than on the middle-class mindset he grew up with — is a winning one for the long term.

As he has built up to his announcement this year, Biden has sought to contrast the policies he has championed against what he casts as the outdated approach of “limousine liberals” who he said have lost touch with the concerns of people like those he grew up with. Too many Americans “have been left behind and treated like they’re invisible,” as he said in his State of the Union address this year, arguing he has begun to change that with an agenda geared toward that middle.

“He’s leading a revitalization of American manufacturing that not a lot of people saw coming. And that’s happening all over the place,” Mike Donilon, one of his closest advisers for decades, said about Biden’s governing approach in an interview before his announcement. “A lot of that’s happening [in] places that have been in hard times for a long time … and he thinks they deserve a shot.”

Incumbents, especially those with as many ominous polling numbers as Biden, are usually keen to frame the election as a choice between two parties rather than as a referendum on their record. But Biden’s team believes his record only makes the partisan choice starker and frames his record in sweeping terms — as the beginning of a reversal of the economic model Ronald Reagan ushered in four decades ago, which was still taking root the first time Biden ran for president, in 1988.

“We’re in a fundamental shift for what has been roughly 40-plus years of economic policy in America. And he’s leading it,” Donilon said. “He talks about trickle-down didn’t work, never worked. And it led to an economy that helped a smaller and smaller slice of the country and left more and more people out. And when you leave people out, leave them out for a long time, and they don’t feel like they have much of a shot, you start to lose them. And he thinks you’ve got to convey this sense that everyone is in on the deal.”

Biden has already been traveling the country touting that record — especially key planks of his economic agenda: the CHIPS Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act, which aimed to lower prescription drug costs and put money behind fighting climate change.

“It’s a choice between a president who’s delivered on a lot of long-overdue promises in American life — to restore middle-class life, to restore manufacturing — and probably an ex-president who promised a lot of that stuff and didn’t deliver,” Klain said. “A president who got things done in Washington versus an ex-president who brought chaos to Washington. So I do think it’s a choice. I think the accomplishments validate what President Biden brings to that choice.”

This may be his last campaign, but advisers say Biden has never looked at it that way. If anything, Kaufman said, his approach now is the same it was in his first Senate campaign in 1972.

“One of the things we learned early on is if you want to get something done you better run on it. He’s never approached a campaign any other way except what is it that I want to do if I get elected,” Kaufman said.

That’s why advisers say Biden is likely to campaign on, among other things, pieces of the Build Back Better agenda that had to be shelved to secure passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, including a permanent extension of the child tax credit, a plan to provide two years of free community college and universal pre-kindergarten.

“When he ran in 2020 he thought he was putting it all on the field,” another Biden adviser said. “So I don’t get the sense he’s looking at this as ‘my final.’ I think he looks at it the other way, which is, I think he thinks there are some things in motion. And he wants to see them through.”

Biden’s final campaign will put his economic vision to the test